Laguna Bacalar, Back in Time

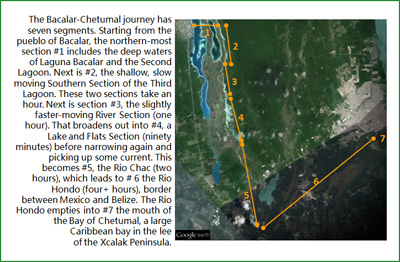

Editor's Note: In his two-day, 49 kilometer kayak trip from Bacalar to Chetumal, our guest writer, Scott Wallace, hoped to find a taste of the rich history of the region in the remarkable and diverse natural beauty one sees today. As you will learn below, it didn't require very much searching.

Laguna Bacalar, Back in Time

Most early mornings, Laguna Bacalar is flat calm before the wind arrives and this morning is not an exception. We launch our kayaks into the rising sun and look back over our shoulders at the 17th century Fuerte de San Felipe on Bacalar's main square. Along the shore we see a dozen or so snail kites. They gracefully overfly the shallow, reedy waters and occasionally dip down slowly to snatch a snail and fly off to feed. In very few minutes, we are away from the shore and head into the deep water of Laguna Bacalar and toward the "Pirate Cut".

Leaving Bacalar pueblo behind, our trip will take us past only a handful of places where the traveler sees anything other than just nature -- very little evidence of humans and fewer signs of contemporary living. The waterway between Bacalar and Chetumal has meandered and in some places changed its course. But the water, the jungle, the wildlife, and the mangroves could be the same as seen by the first Spanish explorers -- and Maya traders for millennia before them.

To Pirate Cut and Second Lagoon

We make our way across Laguna Bacalar's dark-blue, deep (twenty meters) water. Soon we cross some shoals where we see the limpkins feeding, and then are in the fast-moving Pirate Cut. This thirty-meter wide, meter-deep canal drains much of the fifty-kilometer-long lake's outflow, which is sourced largely in cenotes much of the year. The light-blue colors of the water are vibrant with the different depths, the rippling current, and the dappling sunlight. Left and right we see extensive grey mud flats with only occasional low mangroves and lots of bird signs, but few birds. As we drift past a large, low mangrove, we spot two roseate spoonbills on the far side who interrupt their feeding to watch us suspiciously.

Shortly, we enter the deep, darker blue water (fifteen meters) of Laguna Mariscal, sometimes called the Second Lagoon. It, too, is free of wind and waves during our fifteen minute crossing. After scuttling over some flats, we enter a two-meter wide channel that leads to the shallow Third Lagoon. The water is one-half meter deep. We reach the far end of the channel and beneath us can clearly see tapir tracks leading from the edge of a mangrove copse on the left, into the shallow water ahead and straight along the bottom until disappearing in the deeper water of the Third Lagoon entry. We follow and head south.

The Third Lagoon

Completely unlike Laguna Bacalar and the Second Lagoon, these southern waters of the Third Lagoon are slow moving and lead to an infinitude of channels, side-bays, islands, mangrove swamps, nearly-barren mud flats, and reed beds. Bromeliads and occasional orchids hang over the crystal-clear waters and a low mist is drifting around the many islands, inlets, and mini-peninsulas. Looking west, we can just see communication towers over Bacalar and some taller buildings. But our tether to the present is about to be cut.

Quietly drifting and slowly paddling, we make our way south with the current. In the course of ninety minutes, we move like ghosts on the water, slowly creeping up on cattle egrets, little blue herons, white-tipped doves, great blue herons, green kingfishers, green herons, red-billed pigeons, tiger herons, belted kingfishers, tri-colored herons, limpkins, swallows, kiskadees, social fly catchers, ringed kingfishers, more snail kites and a sizable flock of very startled cormorants. Away from us and back in the low jungle, we hear other birds calling.

The sun is burning off the last of the mist as we exit these broad shallows and enter a narrower, mangrove-lined channel with more defined current. Five wood storks glide lazily overhead, making for their island nesting roosts. A solitary turtle plops into the water from a low-hanging mangrove. A heron flies north. The time goes by unnoticed and, were it not for many remarkable photos, this passage might be a dream.

Just ahead of us, the Third Lagoon joins the outflow of the Second Lagoon. We drift into the relatively swift current and are borne south on the River Section of the journey. The water is clear, a meter deep, with a very light turquoise tint and the bottom a combination of rock and sandy mud. Small fish dart away from the shadows of our kayaks and paddles. Many smaller birds -- fly catchers, swifts, swallows and others -- are feeding over the river and socializing at the water edge. We can see large flats off to our right, easily accessible from the main flow through side cuts and around sand bars.

The river narrows and picks up speed a bit. Soon we are traveling through a section with large rock formations sticking out of the water, almost volcanic in their appearance. There is a central channel of water moving nicely but we are wary of the sharp, jagged rocks that punctuate the flow. The banks are fairly close, and the water rocky and shallow away from the center. It is a comfort to emerge from this section into a more easy-flowing stretch of river and to see multi-colored blue water widen out ahead of us.

Lakes and Flats Section

The Lake and Flats Section meanders with enough islands and inlets to disorient the traveler and obscure the way. In size, it is less than a kilometer at the widest. The waters are very clear and the sunlight is bright off the shallow bottom. Near an island, we spot a large, adult osprey flying some meters overhead with a twenty-five centimeter fish aerodynamically held immobile in both talons. It's large wings stroke slowly and gracefully as it powers away from us and toward the far jungle.

We continue around a peninsular toward large, shallow flats that occasionally narrow into a few slightly-deeper channels. As we pass another island, a small brownish hawk sits in a medium-height mangrove on the shore, not five meters from us. We silently watch each other; then the bird takes flight and we see that it, too, has prey -- a very tiny fish clutched in its right talon. Soon, on our right, a spoonbill flaps noisily into the air and away.

Rio Chac

As the Flats Section narrows, the channel deepens to two meters and is perhaps twenty meters in width. In this Rio Chac section, the water remains quite clear. Ahead, we can see stout posts sticking out of the water in a line across the channel. As we approach, a fisherman wades across the stream holding out of the water a large, fabric sack nearly brimming with fish, including a five-kilo jack up from Chetumal Bay. He hangs his bag on one of the posts and lowers the fragile net that stretches from bank to bank for us to pass. Later in the day, he will retrieve his net leaving the passageway free for fish and boats.

The waterway narrows further and mangroves overhang our path. It is quiet and still as we drift and occasionally paddle to avoid branches above and below the water. From time to time, the mangroves recede and the Rio Chac widens with side channels that push the trees back and away from us. We see a few riverside palapas and small private or public picnic and swimming areas. The mangroves are still low here. There is lots of sky and lots of sun. The gently moving waters are cool, clear, blue and inviting.

Rather quickly it seems, we are upon the small channel that connects the Rio Chac to Laguna Milagros, a pleasantly-colored freshwater lake and our destination for the night. We paddle hard to enter against the flow. Fifteen minutes later, the small channel opens up to a one-and-a-half kilometer wide, mangrove-lined lake that narrows to a point about four kilometer ahead. A flock of blue-winged teals is paddling not far away. Some of us set up camp and some stay in cabanas for the night. Together we enjoy a pleasant, sunset sky and then a nice lakeside restaurant dinner before turning in.

The Next Morning Near Chetumal

Not long after first light, as we wake and prepare to head off, the lake is abuzz with kayaks, canoes, and other small water craft. Most paddlers are from nearby Chetumal, taking advantage of the early morning cool and the Olympic race course laid out in Laguna Milagros' center. Heading toward the lake exit and the channel to the Rio Chac, on our left sits a very large flock of cormorants, perhaps the same startled out of the Third Lagoon yesterday.

Soon we are back in the Rio Chac and paddling our way between narrow, tree-lined channels and open, deeper sections with reedy shores. Before long, the flow slows, the channel widens abruptly and we are looking ahead and left and right onto the eighty-meter wide Rio Hondo.

We enter the Rio Hondo's deep (seven meter), dark waters and are struck by the height and vigor of the jungle. The spare, dense soil that surrounds the Laguna Bacalar system has given way to rich, deep earth and the same species of mangroves we saw only a few kilometers north are tens of meters taller here. Admiring bromeliads and orchids, we drift slowly along the tall mangroves that hang over nearly all of the river's shore leading to the Bay of Chetumal. It's easy to feel lost in time and our dream of finding some history alive in the present is coming true before our eyes.

At exactly this moment, coming up the river, we first hear, then spot a boat directly out of the Bogart-Hepburn film, 'The African Queen'. As we paddle closer we see a grey, well-maintained, sixty-year-old (that's our guess...) Mexican Navy supply vessel heading upriver (see banner above). We deduce that it is probably going to La Union to stock a base there. We have our passports and documents at ready, anticipating a request to present them. (The river is an easily-crossed border between Mexico and Belize.) But the men are on a different mission and just wave. The vessel steams upriver and back in time. We paddle south, along the unspoiled banks of the Rio Hondo.

Aside from two bridges, a Navy base, a couple of boats, and a few homes (some in repair and some slowly returning to the earth), there is nothing but jungle or low selva along the entire twenty-seven kilometers to the Bay. It is spectacularly beautiful and solemn, with occasional birdcalls and egrets, night herons, and great blue heron fishing, as trogon fly among the branches. We drift and paddle. On several occasions, a kingfisher hovers meters above the water then plunges with a ka-chug sound to emerge moments later, a fish in its bill. But the best is, literally, around the bend.

A Riverside Puzzle and a Surprise

We come to a riverside quinta (country home) in good repair and are admiring the gardens. Suddenly, we notice in the water beneath us at the river edge two long, narrow, sunken barges. One is forty meters long; the other about half that. We hail the owner and ask about the boats. He explains that about ninety years ago, a sidepaddle steamboat pulled the barges, one at a time, loaded with wood from Bacalar to this spot. Then, six barges would be rafted together and steamed down the Rio Hondo, up the Bay of Chetumal, and out to the Xcalak peninsula, where the wood would be transferred onto ocean-going vessels. The idea flummoxes us. Forty-meter barges loaded with many tons of wood pulled by a paddle wheel steamboats down the route we just navigated? Some parts of that river were not three meters wide nor one-half meter deep. We thoughtfully continue downstream along the tall jungle.

At one particularly wide spot in the river where the west bank is flanked by chit palms rather than the towering mangroves, two manatees surface not forty meters ahead. They are dark, grey-brown in color, and disarmingly slow-moving as they breach to breathe, and then submerge. They surprise us and we sprint toward them. Both of them definitely look large. From our low vantage, it's difficult to judge but we agree they are four meters long. We circle near the spot their tails go under, hoping to see them below or when next they surface. But the water is dark and deep. Although we stay in the area for a while looking up and down river, that first glimpse of these two creatures is our only view.

Rio Hondo to Chetumal Bay

We pass many kilometers of river bank that are completely devoid of evidence of human beings. There are no clearings in the trees, no docks, no small boats, no cultivated fields, no planted tree groves, no small roads to the river, and no trash. Until now, our travels on the Rio Hondo could have been centuries or even millennia ago. Only the Navy supply boat (and a Rio Hondo river tour boat) have broken the spell.

Then, about five kilometers from the Bay of Chetumal, we feel our paddle journey start to change. The wind (which for most of two days has been at our backs and today is with the river flow) shifts a full 180 degrees. If we pause in our paddling now, we drift upstream, away from our destination. The closer we get to the bay, the stronger the headwind. It has taken us four easy hours to travel twenty-two kilometers on the Rio Hondo to here. It will take us half that time in an increasingly hard slog to make the last five kilometers.

Just one kilometer from the Bay, in the river center, at a spot where generations have fished, we come upon a man in a small boat who is slowly working a large tarpon by hand. He tells us he has been at it for half an hour so far. His line angles far out into the water, suggesting a lot of length, and the man is hauling it in hand over hand. From time to time, he pauses as the fish gathers strength and pulls the boat downstream or toward one bank or another. We stay with the fisherman long enough to see his two-meter tarpon break the surface twice and then we continue on our way. About twenty-five minutes later, as we approach the Bay of Chetumal, he motors past us with a grin and an enthusiastic thumbs-up gesture, a different outcome for this particular Old Man and the Sea.

Heading Home

At the head of the river, obscuring the Bay of Chetumal, lies Vulture Island. We paddle left, past the island which is populated largely by black vultures and some egrets. We continue paddling into the shallow waters of the Bay. Not a meter deep, the brackish water appears clear and gives us a bit of the Caribbean blue color that we can see much further out on the horizon. We soon haul out, pack kayaks and gear in the truck, and drive north and home on Highway #307.

In thirty-five hours, we have taken a trip through the past and into the heart of a practically pristine ecosystem that still lies between Laguna Bacalar and the Bay of Chetumal. Just thirty-five minutes later, we arrive in Bacalar pueblo. In an ironic nod to our return to modern life, we eagerly upload photos of our excellent adventure and begin downloading electronic details to catch up on the last day-and-a-half of our lives. It seems we were traveling somewhere out of time.

****

This is the second of three recent articles on Laguna Bacalar by Bacalar resident Scott Wallace. The final article will cover the 74 kilometer Paddle Marathon at Laguna Bacalar this May 2nd and 3rd. For more info on the Bacalar Paddle Marathon, visit www.paddlemarathonlagunabacalar.blogspot.mx/. Scott wishes to extend a special thanks to Gunnar and Jacqueline of www.activenaturebacalar.com for their professionalism in guiding and presenting information about the plants, animals, geology and history of the larger Bacalar ecosystem. It was a pleasure to share their enthusiasm for adventure and their passion for the natural beauty and wildlife of the Laguna Bacalar area.

Read the first article, Laguna Bacalar, Special Waters

Read the third article, Laguna Bacalar Paddle Marathon