David Sterling Talks About His Cookbook

YL: Were you ever professional employed as a chef or in the food business before you came to Merida?

David Sterling: In the late '70s I worked part time on a very low rung of the ladder (pantry) at a French restaurant in Southfield, Michigan. I did that to support myself while pursuing a MFA in design from Cranbrook Academy of Art. In just two years, I developed a loathing for hands-on work in the restaurant business and never went back. However, I did take my skills and apply them to my own little catering company, serving friends and acquaintances, which I operated casually for a couple of years after graduate school. Later, in my design and marketing business in New York, many of our clients were in the food industry; we designed identity, packaging, signage, even some interior spaces for restaurants and packaged foods enterprises. While the French training I received at the restaurant has served me well, nothing could have prepared me for the lessons to be learned in the humble kitchens of Yucatecan women.

YL: What does it mean to be part of the William and Betty Nolin Series?

David Sterling: My publisher, the University of Texas Press, would be identified as an "academic publisher" rather than a "commercial publisher". As such, they receive grants from various non-profits to publish many of their books. Mine was lucky enough to be sponsored by William and Betty Nolin whose particular area of interest is the art, history and culture of the Western Hemisphere. Diana Kennedy's Oaxaca al Gusto is part of the same series.

YL: Did you enjoy the process of writing a book? What was the hardest part about it for you?

David Sterling: The process of writing the book was exhilarating, if at times exhausting. I was so obsessed with it (and harried by deadlines!) that I would often – almost daily – wake up at 4 AM and start clacking away at the keyboard. And the work continued until the early evening, weekends included. It is rather like dealing with a hurricane or some other force of nature: The Book loomed ahead of me on the horizon and I really could do nothing but write and think about it, not to mention the hours of historical research and all the interviews and travel it required. And let's not leave out the recipe testing. In light of my obsession, it might not be surprising that the hardest part of writing the book was getting to the end. I developed a major case of postpartum depression on the day I submitted the final galleys. Thankfully, I was able to commiserate with Diana Kennedy, and she told me the same thing always happens to her, and that the only remedy is just to start writing another book. And that's exactly what I did.

YL: It seems you traveled a lot around the Yucatan Peninsula to research this book. What was your most treasured experience that you remember from those travels?

David Sterling: There are so many, but the one that leaps to mind is the scene in Tetiz where doña Sara taught me how to make merengues. The process was absolutely fascinating: Italian meringue whipped by hand – in point of fact, the hand of the family patriarch! – is piped out in tidy little domes onto crude paper-covered tables, and then baked from above by placing red-hot coals atop a large steel drum that covers the merengues. But it wasn't just the process... It was being welcomed by the family, and spending time with them. They prepared almuerzo (lunch) each time I visited. Like so many of the women and families I met, they were surprised to discover that a gringo could be so interested in their food, and beyond delighted and generous to share their stories and recipes with me.

YL: OK, this is just curiosity... you say that the panucho of today "bears only a faint resemblance to its predecessor of the 1950's"... what would a 1950's panucho have looked like?

David Sterling: The original panucho evolved in the early 20th century as a means of making use of leftovers. By Wednesday, Monday's frijol con puerco had been stripped of all the meat, so creative cooks puréed and strained the leftover beans to make frijol colado – which then became the filling for panuchos. The creamy purée was put into the hollow of a fresh tortilla along with a slice of boiled egg, then fried and topped with our ubiquitous pickled onions. Behold! the Primal Panucho was just that simple! I've only seen them still prepared this way in the market in Tixcocob. As you might imagine, they are ridiculously inexpensive. By mid-century, the panucho had become so popular that panucherías – shops that sell panuchos – had sprung up across the city and into the pueblos. Naturally, competition increased. So, the next incarnation featured meat – in this case, pavo en escabeche, turkey cooked in vinegar and black pepper with lots of white onions. The invention was surely something to lure customers away from the plain ones with just beans! It is also rare today to find that 1950s version of the panucho, although I have prepared them myself and they are fabulous! Nowadays, folks put on just about any topping: fried shrimp, octopus in its own ink, grilled chicken or relleno negro (turkey in charred chile sauce). The one constant is that tortilla base filled with frijol colado. Even the slice of boiled egg has been lost somewhere along the way.

YL: Where can this book be obtained south of the border if you don't want to spend to have it shipped by Amazon?

David Sterling: In Mérida, they are sold at LA68 gallery as well as at Casa Catherwood. But the only place I can guarantee a steady stock is here at my cooking school, Los Dos. The best thing is to contact us directly at info@los-dos.com to ensure someone is here to receive you – and for me to autograph your book!

YL: This book is amazingly comprehensive... you seem to have thought of everything. Now that the book is printed, is there anything you wish you had included but did not? Anything you decided to leave out?

David Sterling: I submitted a document of 250,000 words. It was whittled down to just 180,000 words for publication. Yes, a lot hit the cutting room floor. A lot of it was best left out – just too much! – although there were quite a few recipes from Valladolid that I reconstructed that I wish could have been included. During my research, I was lucky enough to chance upon a vintage cookbook dating to 1910, full of Yucatecan recipes, mostly unique to Valladolid, entitled La verdadera cocina regional. Coincidental to your question, I have just uploaded two of those "outtake" recipes to our website: Pollos en alcaparrado, a heady stew of ham, chicken and chorizo with capers, raisins, olives and almonds in white wine. And Rosquitas de almendras... something like a marzipan "doughnut cookie" with Italian meringue glaze. I will probably add more of these as time goes on, too, since all of these recipes were fascinating historically, as well as delicious.

YL: I noticed one of the reviews said they wished you would do a book like this for every region of Mexico. I have a feeling you probably couldn't live long enough to do that. Do you have any interest or plans to do another regional cookbook?

David Sterling: Hey, I'm only 35! Well, even if that were true, there is no way one person in a single lifetime could possibly focus as intensely on each region of the country as I did for Yucatán. Furthermore, while my publisher is extremely pleased with the sales of my book, I know from my own perspective, and what I know of Mrs. Kennedy's book on Oaxaca, that broad public interest in these regions is quite limited. The hottest selling titles right now are books that "make Mexican easy" (think "crockpot cooking") and that is not something that interests me. So my expectations of doing another deep, comprehensive regional book and attaining some kind of commercial appeal are quite limited. I was lucky with Yucatán, since it has been on many peoples' radar for the past several years. That said, I do have a few tricks up my sleeve, and as noted earlier, I am hard at work on another book. This one will cover more regions of the country, looking at the cuisine through a special lens and writing in much the same "ethnographic" style as I did for Yucatán. (To say any more would be giving away the show!)

YL: You mention that maybe the key essence of Yucatecan cooking is 'smoke', and yet I have seen press releases about NGO's going to Maya villages, replacing traditional smoky firepits with less smoky stoves. This is done for health purposes, one of which is to avoid asthma in children. Do you think this trend will have an effect on the taste of traditional Yucatecan cuisine in the future?

David Sterling: I applaud those efforts wholeheartedly. I have spent enough time around those fires and come home permeated with smoke to understand the hazards. I have yet to see one of those stoves in use here, but I did just see what must be something similar in Michoacán. They are really quite brilliant, because they are designed in such a way as to permit smoke to touch and flavor the food, and yet to direct the smoke up and away from the cook. The ones I saw were simple affairs made essentially of mud bricks, covered tightly with more mud, with a chimney going up and out. This kept all the delicious smoke where it belonged. But for our own health, if we are going to worry about smoke, we should perhaps worry about the carcinogens that are created during the process of grilling or smoking foods in the first place. I don't worry about it. I just ate dinner at Hartwood in Tulum, where absolutely everything is cooked in a wood burning oven or over a wood fire. I felt that I must be savoring the flavors of 1000 years ago (talk about paleo!) when everything would have been cooked that way. It was the best meal I've had in years. And these new stoves, at least from what I saw in Michoacán, still achieve that lovely flavor. Finally, as I mentioned in that section of the book, a kind of smokiness is imparted to foods in Yucatán in other ways, too, simply because women use well-worn pots that are covered with grease and smoke accumulated during years of duty.

YL: Your book is practically a history lesson about the Yucatan... certainly one that is easily accessible for English speakers. And it is equally a tourist guide. Have you had any government support or overtures that they may help distribute or publicize your book to help grow Yucatan tourism?

David Sterling: I am not a cynical person, and yet I am a realist and have come face to face on many occasions with local bureaucracies. (The same would surely happen beyond Mexico.) In April of 2014, I had a launch and book signing event at Hacienda Xcanatún. We invited top-level bureaucrats in several levels of the government, including Turismo. Not one of them came or sent "regret" messages. We had sent copies of the book to all of them in advance to entice them to come, and to "prove" the seriousness of the event and the book. Recently, I learned that the governor only received a book about a week ago through some other channel. Who knows where that first one went? Word was that he loved it, but that is the last I heard. I do believe that the promotion of Yucatán as accomplished by SECTUR and local affiliates is pretty sophisticated and slick, but it is very standard, good old "Mad Men"-style advertising. They don't really seem to think outside the box. Yucatán has just spent time in Germany and I don't know what other countries at tourism fairs. In my view, boxes of my books should have been there for the promotional value implicit in it.

YL: I notice you mention Sian Ka'an and lobster, and the honey from Felipe Carrillo Puerto, but those seem to be the only mention of anything from Quintana Roo. Are there any other dishes that are native from that very popular area that you did not include?

David Sterling: During the final flickers of the Caste War, Quintana Roo became a refuge for the Mayas as they scattered east to escape the onslaught; Chan Santa Cruz still plays a big role in the region. However, there were two issues with the food that I found there: (1) even when it was really typical "Maya" food, it was rarely something you couldn't find anywhere else in the peninsula, so repetition became a problem; and (2) the closer you get to the coast, the food has become strongly influenced by modern trends. Not that I have any problem with that, but it just loses its uniqueness and appropriateness for a book about Yucatán. But look closer, too! There are at least a couple of other recipes I can think of in the book that are from Quintana Roo: the huachinango in Tulum, and also if you check out the recipe for Queso relleno, you'll see the inclusion of a variation that uses seafood instead of pork, which I found in Playa del Carmen and cite that.

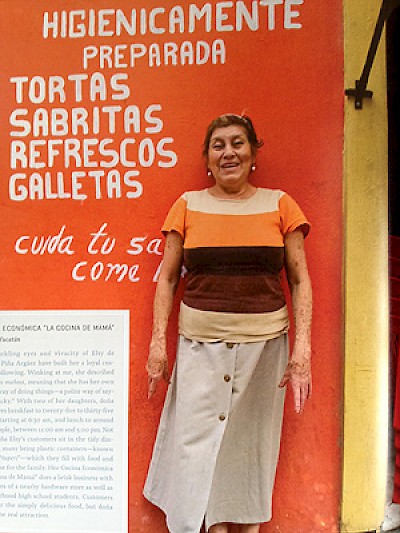

YL: What are your favorite Merida cocina económica?

David Sterling: I have enjoyed so many through the years that it seems unfair to highlight just one. Still, I do have a personal connection with "La Cocina de Mamá" on Calle 70 at Calle 67. It's the one I featured in my chapter called "The People's Food." Doña Elsy is one of the most warm and loving people I've ever met, and she brings a great sazón to her food. Like all cocinas económicas, it serves good, basic home style food with no frills. But doña Elsy is the real attraction.

YL: To which restaurant would you send a first time tourist to taste the best "authentic" Yucatecan food?

David Sterling: Without question, Hacienda Teya. I avoid the word "authentic" in favor of "typical", however. (Is there such a thing as "authentic meatloaf", as just one example?) Teya is totally typical and representative of the cuisine, but most important, it is consistent. That's the unfortunate problem with so many restaurants here... they vary radically from one visit to the next. Teya, on the other hand, never disappoints. Readers should know, too, that the hacienda has a charming, small garden of unique local plants. Allspice, guanábana, achiote, and jícara can all be seen. When I take students there I always grab an allspice leaf from the tree (Pimenta dioica) and crush it. It smells exactly like allspice, and is sometimes used in our cuisine. And if you're lucky, you'll see a little native deer (Mazama species) that occasionally comes fearlessly close to the gate.

YL: Congratulations on winning the Art of Eating award... what do you intend to do with the prize money?

David Sterling: Thank you, it is quite an honor, especially considering one of my culinary heroes, Harold McGee, served as one of the jurors. I have earmarked every peso of the prize for research and travel on the next book.

****

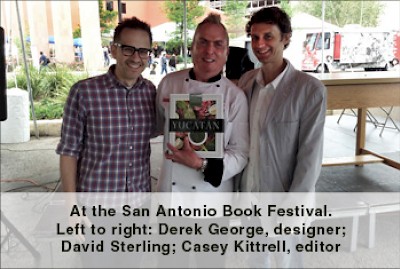

Buy David Sterling's Yucatan: Recipes from a Culinary Adventure here from Amazon.

David Sterling's Los Dos Cooking School.

Hacienda Teya in Merida, Yucatan.

About Harold McGee on his blog about cooking.

Diana Kennedy's website.

Comments

Justin Ellis 8 years ago

Hello, please can you help me? My name is Justin Ellis and I grow chilli pepper plants in England/United Kingdom. I am desperately trying to find a way of buying some 'Xcatik' chile pepper seeds that I can grow plants from here in the UK. I have been unable to find anywhere or anyone that sells them. I understand they a local pepper to the Yucatan and they are grown locally near Progreso and Merida, Please could you help me? I really look forward to hearing from you. thanks you so much. best wishes

Justin

Estoy buscando para comprar algunas semillas de chile de la Xcatik Chilli, para que pueda cultivar una planta, por favor, ¿puede ayudarme?

Reply

(0 to 1 comments)