Yucatan's Connection to Texas

Editor's Note: In this two part series the author will look at the historical relationships between the Yucatán and the Republic of Texas. Byron Augustín is a former professor at Texas State University and we are happy to be the recipient of his research on this subject. Enjoy!!

Introduction to the Texas Connection

Part One of this two-part series will focus on the events leading to independence and the role of Lorenzo de Zavala, a native Yucatecan. Emphasis will also be placed on three major battles at the Alamo, Coleto/Goliad, and San Jacinto. The second part will trace the role of the Republic of Texas Navy between 1835 and 1837, highlighted by the cruise of the Texas schooners, Invincible and Brutus. This cruise spent a significant amount of time in the waters off of the Yucatan Peninsula, where they harassed coastal settlements and shipping in the Gulf of Mexico.

Texas and Yucatan

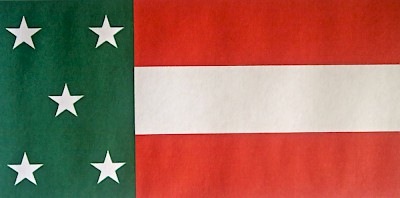

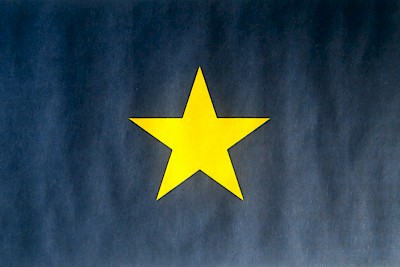

Texas and the Yucatan have many things in common. Both political entities were at one time part of Spain’s Latin American colonial empire. When independence from Spain was won in 1821, the territories fell under the political jurisdiction of the new nation of Mexico. Both the Yucatan and Texas resented the political decisions forced on them by the central government in Mexico City. They bristled at taxes they were forced to pay while receiving few services from the central government. They were both located in remote areas, far away from Mexico City. Both rebelled and declared themselves independent republics. The Yucatan did so twice: first in 1823 for seven months and again in 1841 for seven years. Texas declared its independence in 1836 and was a republic for nine years. Soldiers from the Yucatan attacked Texas with General Santa Anna in 1836 and sailors from Texas attacked the Yucatan in 1837.

Growing Unrest

In 1830, two events occurred that spiked the Texan settlers’ anger and eventually brought Yucatecans into the conflict. First, the central government in Mexico City passed the Law of April 6, 1830. This law restricted United States citizens from settling in Texas. Second, military garrisons were established in Velasco and Anahuac and staffed with Mexican troops. The Mexican Army had orders to impose duties on commerce passing through the area. The Texans were seething at this new development since they had been pressing for lower tariffs.

In addition, many settlers had moved to this area from the southern United States and had brought their slaves with them. Since Mexico had officially banned slavery in 1829, the settlers were worried. They wanted to expand slavery.

Finally, they were furious when President and General Santa Anna abrogated the Constitution of 1824 early in 1835 and essentially changed the presidency to a dictatorship. Vocal Texans openly expressed their disdain for the petty, arrogant, narcissistic bully that led Mexico.

Lorenzo de Avala

Three significant political events that took place in Texas in 1835 and 1836 would help define and shape the move toward independence. One man would play a role in all three events. His name was Lorenzo de Zavala and he was a third generation Yucatecan born in Tecoh, Yucatan in 1788. He moved to Merida as a youth and graduated from Tridentine Seminary of San Ildefonso. Zavala was one of the most brilliant intellectuals of his time. He was a diplomat, physician, writer, philanthropist, and a gentle soul who promoted democratic principles. He was elected or appointed to several political positions, including President of the Mexican Congress. That Congress had approved the Constitution of 1824, a decision and document which guaranteed more freedoms for Mexican citizens. When Santa Anna rejected the 1824 Constitution, Zavala was serving as Mexico’s Ambassador to France. He resigned his diplomatic post in Paris and settled his family on his land grant in southeastern Texas near Houston.

Once in Texas he became an articulate spokesman for independence from Mexico. His first involvement in the three significant political events was as an advocate for a Consultation to discuss the purpose of a war to earn independence, the power and structure of government, and the virtues of various potential leaders. Zavala represented the Harrisburg municipality. His leadership and political wisdom shaped an agreement to establish a provisional government based on the Mexican Constitution of 1824. The delegates voted Henry Smith as provisional governor, Sam Houston as commander of the regular army and the establishment of a four-ship Texas Navy. Unfortunately, the Consultation proved ineffective and was plagued by bitter confrontations between opposing individuals.

As a result, a convention was held at Washington-on-the-Brazos to write a Declaration of Independence for Texas. Once again, Lorenzo de Zavala played a major role in the drafting of the document. Zavala was one of 59 delegates who signed the declaration. He was one of only three Mexican signees, and the only individual born in Mexico. On March 2, 1836, the Republic of Texas officially declared its independence. However, it would remain a part of the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas until it won its war of independence from Mexico.

The Convention then initiated the writing of a new constitution on March 1, 1836. It was completed and adopted fifteen days later, after the fall of the Alamo and four days before Colonel James W. Fannin’s surrender near Goliad. Events were not favoring the new republic and the constitution was a rushed effort. Lorenzo de Zavala’s experience as a statesman with great intellectual ability provided major contributions to the final draft. Delegates were so impressed with his organizational skills and quiet ability to promote compromise and consent, that they selected him as the first vice president (interim) of the newly declared Republic of Texas. History documents that few people impacted the birth of the new republic more than the unpretentious Yucatecan, Lorenzo de Zavala.

Tension and Revenge

As political events in Texas were evolving, Santa Anna sent his brother-in-law, General Martín Perfecto de Cos, to San Antonio. He ordered the general to arrest the unruly leaders of the Texans who were opposing his decisions. Cos occupied San Antonio with a troop of 300 soldiers and was soon surrounded by a large military contingent of Texans. Even with reinforcements and after a lengthy siege, Cos surrendered and his unit was forced to return to Mexico.

Santa Anna was furious. He felt shame and disgrace from Cos’s defeat and vowed revenge against the rebellious Texans. He would have been well advised to remember the wisdom of Confucius, who said, “Before you embark on a journey of revenge, dig two graves.” Santa Anna’s narrow-minded focus on revenge would necessitate the need for a multitude of graves for Mexican soldiers before the revolt ended with an independent Republic of Texas.

The March to San Antonio

Santa Anna immediately began plans to march a large army to Texas and obliterate the disrespectful Texans, who he referred to as piratas (pirates). Some of his advisors cautioned him about the pitfalls that he could face. Weapons, ammunition, gun powder, food, medical supplies and even uniforms and boots were in short supply. The march north would pass through difficult terrain, desert, and sparsely populated areas where replenishing supplies would be difficult. They urged him to wait until spring to avoid the treacherous winter weather. All of their advice fell on deaf ears as Santa Anna was described as a poor listener. Mexican historians later described the foray into Texas as lacking prudence, planning, foresight, and good judgment. But hey, we should not let common sense get in the way of a “mission of revenge”, right?

General Santa Anna named his military plan the "Army of Operations". After he left Mexico City, the column marched north through Querétaro and on to San Luis Potosí. Along the way they added beggars, drunks, jail prisoners, and Indians as forced conscripts. Also included were at least three battalions of Yucatecan Maya, many of who wore light weight cotton clothing and sandals. They spoke Mayan, not Spanish, and could not understand the orders of their Spanish speaking officers. No group suffered more or lost a higher percentage of their original numbers than the Yucatecan Maya on that march.

The march north was in many respects a death march. Medicine for the sick was scarce; food was limited essentially to one-half (eight ounces) of a daily ration of hard tack, a rock hard corn biscuit that did not provide proper nutrition. The health of Santa Anna’s troops declined steadily. By the time they reached Monclova, they were facing a 300-mile, 12-day march to San Antonio through a hostile arid and semi-arid environment. Water supplies for the soldiers, cavalry horses and oxen pulling the supply carts became scarce. Limited watering holes were frequently contaminated with decaying dead animals or had been fouled by the Comanche and Apache Indians. The Indians posed a constant threat by raiding the periphery of the camps and scalping unsuspecting and exhausted soldiers. They also followed the stragglers, killing them when their physical conditions rendered them incapable of fighting.

Death Comes With a Norte

By the time the Army of Operations reached the Rio Grande River, hundreds of men had perished... perhaps as many as two thousand. On February 13, 1836, a classic “blue norther” pushed frigid arctic air into Mexico. The dramatic drop in temperature led to infected throats and respiratory systems, fevers, aching joints and weakness. La Gripa and pneumonia spread rapidly among the troops. General José de Urrea wrote in his diary that the Yucatecan Maya conscripts marched through snow in their sandals, and suffered and perished in large numbers due to their exposure to the cold. He specifically noted that the Maya Indians were accustomed to the tropical climate of their native peninsula and that their bodies could not adjust to the dramatic climate change. Documentation of an accurate number of lives lost does not exist, but many historians speculate that more soldiers died on the march than in battle. Meanwhile, Santa Anna, “the Napoleon of the West,” rode in the comfort of his luxury coach, ate his meals on fine china, and drank wine from crystal glasses.

The Alamo

Santa Anna began his siege of the Alamo on February 23, 1836. His cannons pounded the walls of the fortress, weakening the structure. By March 5th, his troop numbers reached an estimated 1,400. At 5:00 A.M. on the 6th of March, the Mexican army began its assault. Many Yucatecan Maya were in the front lines and died while rushing into a heavy barrage of cannon and rifle fire. All told, it is believed that nearly 600 Mexicans died in the span of ninety minutes. The 189 Alamo defenders all lay dead, including seven survivors who were executed.

The Goliad Massacre

While Santa Anna prepared to chase most of what was left of the Texan army, General José de Urrea was moving toward Goliad, winning consecutive victories at the Battle of San Patricio, Agua Dulce Creek, Refugio and Coleto. General Urrea’s troops forced Colonel James Fannin to surrender at Coleto, but only after Fannin secured Urrea’s assurances that his men would be treated as prisoners of war and not executed. Urrea sent Santa Anna a message describing his agreement with Fannin and urged him to honor the clemency agreement.

Santa Anna replied, ordering the immediate execution of those “perfidious foreigners.” Since General Urrea was in Guadalupe Victoria, the execution order was delivered to Colonel José Nicolás de la Portilla, the Commanding Officer at Goliad. Colonel Portilla followed Santa Anna’s orders and at dawn of March 27, 1836, the prisoners were marched to a grassy area outside of Goliad and executed by a firing squad. Fannin and injured soldiers were shot at the Presidio de la Bahía. The firing squad was composed of several Maya infantry soldiers who were members of the Yucatan Battalion. A report after the execution stated that Colonel Fannin’s command lost 342 individuals. Twenty-eight prisoners escaped into the woods under cover of the smoke from the heavy gunfire. A nurse, whose husband was a Mexican doctor, hid some of the men who survived. Her name was Francita Alvarez, and she is remembered as the “Angel of Goliad.”

The Goliad massacre of defenseless soldiers and the extermination of the defenders of the Alamo cast a shadow over the humanity of Santa Anna and the Mexican people. The reaction of Texans, Americans, the British and the French was marked by livid anger and helped contribute to the success of the Texas Revolution. Less than a month later, Santa Anna and his army would experience the truth in the saying, “what goes around, comes around.”

Remember the Alamo, Remember Goliad

After the fall of the Alamo on March 6, 1836, General Sam Houston began a retreat toward east Texas recruiting new soldiers and collecting some reinforcements. By the 20th of March his army had increased to 1,200 men. The men were poorly trained and poorly disciplined. Houston was convinced they were not ready for battle. As he continued his retreat, Santa Anna remained in hot pursuit determined to teach the brash, insolent Texans a final lesson and quench his own thirst for revenge.

On March 25th, Houston and his troops received news of the Goliad Massacre. Twenty-five percent of his army either deserted or returned to their homes to help their families flee. The remaining soldiers complained loudly about making a stand and began to openly criticize General Houston’s strategy. Still, Houston moved eastward. On April 11th, the Texans received two-six pound cannons dubbed the “twin sisters” as a gift from the citizens of Cincinnati. In the forthcoming battle, those sisters would be the only artillery available to the Texans.

On April 18th they learned that Santa Anna was in a position near the San Jacinto River. The next day approximately 900 Texans crossed Buffalo Bayou and took up a position opposite the Mexican encampment. On April 20th, a minor skirmish occurred but not a full battle. Early on April 21,1836, General Martín Perfecto de Cos arrived with 540 reinforcements bringing Santa Anna’s army to nearly 1,300 soldiers.

Onward to Independence

The Texans protected by a high ridge crept slowly forward until they were within 200 yards of the Mexicans. The “twin sisters” were wheeled into position facing the center of Santa Anna’s ranks. General Houston reminded the soldiers to “Remember the Alamo, and Remember Goliad.” At 3:30 in the afternoon, all was quiet as the exhausted Mexicans were deep asleep in their traditional afternoon siesta. There were no sentries. Suddenly, the “twin sisters” belched fire and smoke as handfuls of musket balls, glass fragments and horseshoes ripped through the Mexican camp. Nine hundred enraged Texans, screaming, “Remember the Alamo and Remember Goliad” fell upon them like a pack of rabid dogs, with rifles, pistols, bayonets and knives. In eighteen short minutes it was over. Houston later reported 630 dead Mexicans and 730 prisoners, many of them Yucatecan Maya. Only nine of 910 Texans had been killed or mortally wounded and 30 were less seriously wounded.

Santa Anna actually escaped during the battle by wearing a conscript’s uniform. He was captured the following day. The Republic of Texas had secured its independence.

*****

Read Part Two of the Yucatan's Connection to Texas here.

Comments

Charlie Franz-Harrigan 8 years ago

I also am a graduate of Texas State University. Also known for us old timers as Southwest Texas State University. I am an expat living in Rio Lagartos for the past four years. Loved this article.

I have family of eight, yes eight generations of Texans. I knew when I first came to the Yucatan it had a special meaning. Thanks for the connection.

Regards,

Charlie

Reply

(0 to 1 comments)