Yucatan Sisal in History

A few months ago, we found this printed advertisement for Yucatan Twine on eBay while searching for anything related to Yucatan. We had it sent here to Merida and framed it, and it now sits in our office. The other day, we were reading it again and thought that we would share it with our readers, as it really is an interesting peek into the shared history of the United States and the Yucatan Peninsula.

The Country Gentleman

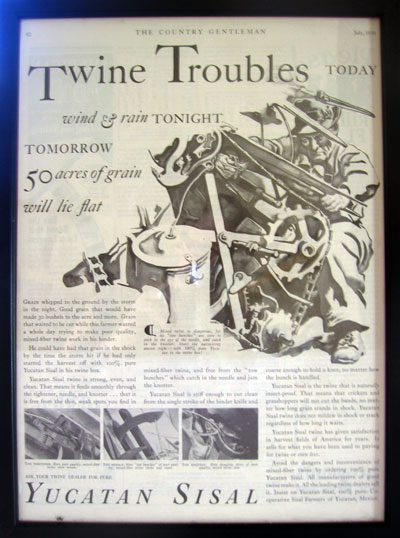

The page is an ad in a magazine called The Country Gentleman, dated July, 1930. The Country Gentleman, according to Wikipedia, was an agricultural magazine founded almost one hundred years earlier in Rochester, New York. By 1955, it was the second most popular agricultural magazine in the United States and was eventually merged into Farm Journal, now the largest U.S. farm magazine.

In 1930, the Country Gentleman was a well-established and respected magazine among farmers, not only due to its editorial content, but also because of many covers that had been painted by Norman Rockwell over the preceding ten years. In the months leading up to July 1930, articles had included "Chain Banking and How It Is Likely To Affect Agriculture", "Making Flying Pay", and "Some Ifs in Rural Electrification".

Yucatan in 1930

A quick review of Yucatan history shows that in 1930, Yucatan was being heralded in an article in the Christian Science Monitor as "one of the few truly socialistic states in the world". Explaining that the government rules in both politics and business, it says "This unity of business and political power makes the state one of the strongest in the Mexican union. It is important economically to the rest of Mexico. In spite of being one of the smaller states and located at the tip of a hard, rocky peninsula almost bare of earth, its efficient organization makes it one of the first contributors to the national budget." The article goes on to explain that the henequen growers had formed a collective, whose president was the governor of the state of Yucatan. The article says that henequen is Yucatan's chief product and chief support, with the US, its chief buyer, taking 90 percent of everything Yucatan produced. At that time, Yucatan still had a world monopoly of the product, according to the article, with Manila hemp its only and poorer rival.

What Makes Yucatan Sisal So Good

So, now, with the stage set, here is the text of the ad that is pictured below, that ran in July 1930 (one month before the magazine cover pictured above), advertising Yucatan Sisal to the American farmer:

"Twine Troubles Today - Wind & Rain Tonite

Tomorrow: 50 acres of grain will lie flat

Grain whipped to the ground by the storm in the night. Good grain that would have made 30 bushels to the acre and more. Grain that waited to be cut while this farmer wasted a whole day trying to make poor quality, mixed-fiber twine work in his binder.

He could have had that grain in the shock by the time the storm hit if he had only started the harvest off with 100% pure Yucatan Sisal in his twine box.

Yucatan Sisal twine is strong, even and clean. That means it feeds smoothly through the tightener, needle and knotter... that it is free from the thin, weak spots you find in a mixed-fiber twine, and free from the "tow bunches" which catch in the needle and jam the knotter.

Yucatan Sisal is stiff enough to cut clean from the single stroke of the binder knife and coarse enough to hold a knot, no matter how much the bunch is handled.

Yucatan Sisal is the twine that is naturally insect-proof. That means that crickets and grasshoppers will not cut the bands, no matter how long grain stands in shock. Yucatan Sisal twine does not mildew in shock or stack regardless of how long it waits.

Yucatan Sisal twine has given satisfaction in harvest fields of America for years. It sells for what you have been used to paying for twine or even less.

Avoid the dangers and inconvenience of mixed-fiber twine by ordering 100% pure Yucatan Sisal. All manufacturers of good twine make it. All the leading twine dealers sell it. Insist on Yucatan Sisal, 100% pure. Cooperative Sisal Farmers of Yucatan, Mexico"

The illustration in black and white is uncredited, much to our dismay. The caption reads "Mixed twine is dangerous, for its "tow bunches" are sure to stick in the eye of the needle, and catch in the knotter. Start the harvesting season right - with 100% pure Yucatan in the twine box!"

The article in the CSM describes the "feudal economic organization" that existed in the Yucatan, ruled by rich "henequeneros" before Felipe Carrillo Puerto came along and translated the free constitution of Mexico into the Maya language for the benefit of those who did not speak Spanish. Carrillo Puerto also formed the first of the "leagues of resistance", which at the writing of the article, ruled the state of Yucatan. These leagues were not just political organizations, but also clubs that promoted social and educational activities. The article described cultural evenings in the pueblos, as well as one in Merida held on Monday nights. In Merida, there was "an extensive program, at which the leading thinkers and workers in various fields give talks and lectures, at which local talent in music and art donate numbers... When programs are especially interesting the overflow congregates on the streets outside and the speeches and music are transmitted by loudspeaker. Sometimes these are in Maya, the native Indian language of the State, which almost every Yucatanian knows, even the first families." The article ends by mentioning the unusually large participation of women in all these events, and how clean everything and everyone in Merida was!

Well, Not Quite...

What's odd about this article is that by the time it was published, Felipe Carrillo Puerto had been dead for over six years. He, along with three of his brothers, a former Yucatan governor named Manuel Berzunza and three others, were shot by firing squad in 1924 during a brief and ultimately failed revolt by Adolfo de la Huerta. Most of Carrillo Puerto's "social experiments" were overturned or ignored for a time, but they returned in earnest when land and sometimes entire haciendas were granted as ejidos to the Maya workers under subsequent socialist administrations. Policies of agrarian reform and support of the working class reached their apex in the 1930's under the Presidency of Lazaro Cardenas, which put an end to the fortunes of the "henequeneros" and their culture.

These policies did not produce the expected results and are often blamed for the decline of the sisal industry in Yucatan. However, historians point out that the poor management of some collectives was only part of the problem. Several hacienda owners chose to abandon their holdings when the revolution arrived in Yucatan after 1915. Others had overinvested, borrowing heavily during the boom, but finding themselves unable to repay after the bust, when the price of sisal declined following the stock market crash of 1929. They, too, walked away from their property (sound familiar?). During the 1930's, there was a "Great Depression" in the United States, not the best time to expect increased exports to American farmers. But the real turning point came when Yucatan sisal had to compete with other less expensive fibers, which is undoubtedly why the advertisement above was published in the Country Gentleman all those years ago.

The whole article from Christian Science Monitor, April 24, 1930 (.pdf)

Farm Journal history, from their website

Comments

Working Gringos 15 years ago

Tom: Yute is the Spanish name for Jute, a coarse vegetable fiber commonly encountered as burlap but also used for clothing. Although it is grown in Mexico, we've not seen it in Yucatan State.

Reply

tomjones 15 years ago

Enjoyed this article tremendously. Provides great historical perspective to use of sisal. Would like to see a follow-up of contemporary usage. We recently brought to the States as gifts the attractive "reutilizame" shopping bags of Soriana - "por el Mexico que todos queremos." Is "yute" the same as henequen? Tom Jones

Reply

J.D 15 years ago

Thank you so much for so much hitory! My Father used to work in those fields in the pueblo of tixkokob. My relatives still live there and they still have a few plants of henequen. But I never knew how important that kind of industry was. I will relate this information to him, I am sure he will find it intersting and will bring back memories. Thank you again for enlightening not only foreigners with your articles, but also the natives like me.

Reply

« Back (10 to 13 comments)