One Last Effort: Chapters Thirteen & Fourteen

XIII

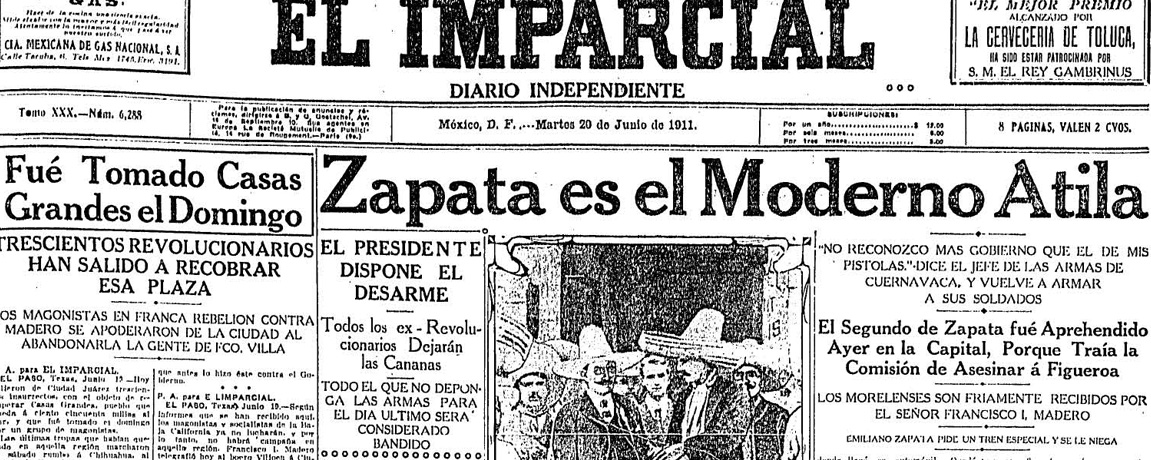

The government’s four-year term was coming to an end and the employees, as well as those who hoped to become such, were already scrambling in the serious mission of determining who should replace the head of State.

There were two camps, each with its respective candidate. The first took the name of Gran Partido Liberal and the other, wanting to be no less, that of Gran Partido Liberal Porfirista. Despite the similarity of their names seeming to be based on their similarity of principles, they had a field day thrashing each other in their newspapers, opponents hurling a veritable avalanche of insults and epigrams at the respective candidates.

None of this would be important to us if our friends had not entered into the matter.

Señor don Felipe Ramos Alonzo was the main editor of one of the publications of the Gran Partido Liberal Porfirista and had gone to great lengths to finally convince don Hermenegildo that it would not hurt him to take on the management of that echo of public opinion.

“And what’s more,” he said to the bachelor, “on the day of triumph, the governor, who will know who worked in his favor, will give you a cut when it comes time for redistribution.”

“But do you think victory is likely?”

“Likely? Certain. Do you know who supports us in Mexico City? Among others, the Ministers of Government and Development, who you well know have a decisive influence on the President, who in addition knows and likes our candidate very much. We’ve learned that one week from now the opponents’ commission will be leaving for the capital, but we’ve already won the lead by appointing the Yucatecans who are in Mexico City, and on day four they should be presented to the Prime Minister of the Republic by the two Secretaries. You’ll see the letters on the next ship. All done; we win the elections.”

“But surely you’ve noticed that some of the capital’s dailies don’t appear to be very favorable. Believe me, I know what I’m talking about.”

“That doesn’t mean anything. They don’t know what’s going on here and they publish what they’re paid for. José D. Góngora is charged with seeing to it that various stories sent to them appear in print, and there will be no shortage of newspapers that welcome them and promote our candidate and passionately defend him.”

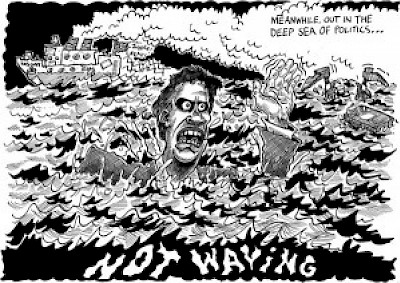

And so it was that our retiring fifty-year-old entered into the tumultuous sea of politics toward which he had formerly held a passive stance. He would make the commitment and his name would appear as manager of “La Aspiración Popular,” giving rise in his heart to a great affection for the candidate he barely knew.

At those times when the messenger regarding something from the opposing camp stopped by to deliver the obligatory update, Hermenegildo devoured the print as if in it they were notifying him of a pay raise, and the vicious attacks directed at his candidate left him as hurt and indignant as if they had been written about his father.

Among those who contributed to the support of the newspaper was Pancho Vélez, a relative of “La Aspiración Popular’s” candidate, and he could often be seen in the editorial office. What sparks and spluttering flew from his eyes and mouth when he heard the insolent remarks that mob made about his uncle! What threats he made to break one guy’s ribs or to wring that ungrateful wretch’s neck, when if they had a job, it was due to the work and grace of the same man they were now insulting.

The editors calmed him down, telling him that they would get even soon enough, to say nothing of the fact that the poor wretch, with the tuberculosis that was consuming him, was in no condition to go on the offensive.

Don Hermenegildo had been presented to the governor-in-the-making. With some frequency he went to pay an evening visit to him, who was always surrounded by many people, all of them desperate to bring good fortune to the State. Never did the bachelor utter a single word denigrating those who represented the other party and all his strategy consisted of praising his own.

What good people! How they deplored the fact that the separate branches of public administration couldn’t function in a way that corresponded to the culture that that important sector of the Republic had achieved.

And their Leader? What an excellent individual! If they won, and of course they would win, you would see what they stood to gain because he would put into practice his grand plans for the State’s progress. His great merit and importance were well noted because the most respected people hung on his every word. And when he was ready to smoke a cigar, more than one of his visitors hurried to take a box of matches from their pockets to offer him a light.

Don Hermenegildo looked at him and listened with the devotion the oracles would have shown the fortuneteller in the temple of Delphi.

It shouldn’t be thought, due to this new turn in his life, that the clerk forgot his old friends. He no longer went daily to doña Raimunda’s gathering, but he could often be seen there chatting for a while. He also visited Lupita, thereby finding food for his querulous spirit’s appetite in the lamentations of the poor girl, who saw the death of her husband rapidly approaching. But clearly, his principal occupation, after his obligations at the office, was the management of the newspaper and the candidacy of the Leader of the Gran Partido Liberal Porfirista.

At first he worried, despite assurances given him by the señor licenciado, that he would be defeated by all this. But time was passing and issue upon issue came out, many of them sizzling, and don Hermenegildo hung in there without anyone removing him from his position.

The same press that printed “La Aspiración Popular” also brought to public light “El Voto Libre” and “La Voz de Ocampo,” both with the same claims and written by the same people, although varying lists of collaboration could be seen on the front of each one. Many of the articles that could be found in this one appeared in the other, with little more to distinguish them than changing galleys and placing at the foot of them the name of the first newspaper that published them, or preceding them with some version of the following words:

“Our illustrious and courageous colleague ‘El Voto Libre’ brings to light the following article we are pleased to place here, as in it can be seen the shameful means utilized by the competition to raise their candidate from the depths of disrepute in which he finds himself and their attempt to obliterate the enthusiasm with which our own is acclaimed by all.”

XIV

As election time was approaching, the parties attacked each other more viciously. Commissions and letters came and went to the metropolis, and the arrival of the ships coming from Veracruz was awaited more eagerly than if they were carrying manna in their holds.

With only five days before the people would elect the one who would govern them, the mail that arrived from the capital must have carried something very important because it gave great enthusiasm to those who made up the Gran Partido Liberal Porfirista and left those of the Gran Partido Liberal down in the mouth and down in the dumps.

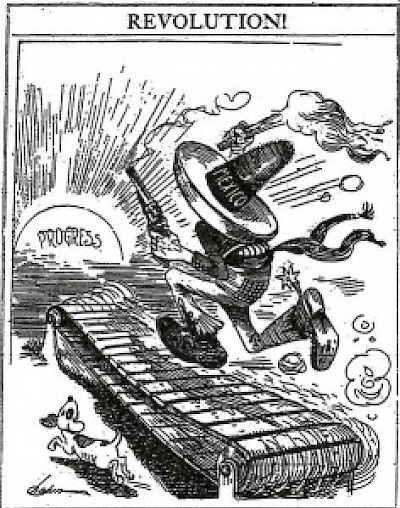

The campaign was won thanks to the work of señor don Felipe Ramos Alonzo and his companions. Therefore, the constituency would turn to the persons they had proposed for the Government.

Poor Pancho Vélez had not been able to enjoy his uncle’s triumph. Bit by bit, he continued deteriorating until he died at the end of September.

And the other side’s candidate? Would he have no consolation in his political failure? To be certain, nothing could be confirmed, although one person related that someone well acquainted with national palace secrets had written him that a Senate seat was reserved for him, as he, like the victor, was such a good friend of the president.

Señor don Felipe would be the local Member of Congress, a position which he preferred to that of Superior Court Judge, as it was more comfortable and because it wouldn’t prevent him from practicing his profession, hereinafter the more promising since his influence in the government would attract business. Besides the corresponding salary, it was later learned that the position paid one hundred pesos a month for service on a commission, which the outgoing party confirmed in the official newspaper, although no one knew that the commission was so comfortable that it took up no more of the lucky winner’s time than what was necessary to write out the receipt.

Naturally, our don Hermenegildo didn’t fail to benefit from the triumph, either, as he went from clerk to a more important office, where he put in only three hours a day in exchange for sixty pesos a month. He also gained the duty of inspector of who knows what, authorized by City Hall, that would give him a salary of fifty pesos. One hundred and ten pesos that he owed principally to the efforts of his unsurpassable friend señor don Felipe Ramos Alonzo, who also offered to give him abundant and well paid work with papers in his office. These were all steps forward that led the clerk to find himself in little less than abundance, comparing his present situation with the desperation of his former life.

Luis Robles returned from Mexico City a little after the new government took over. He came with his usual good humor and a more imposing presence than he had left with.

He had worked diligently as an agent of the triumphant electoral club, seeing that correspondence was placed in various newspapers, which were paid well, proclaiming the immense popularity of the most “honorable and eminent liberal who was called by his fellow citizens to govern the destinies of the people who acclaimed him everywhere.” The same that was said about the other candidate.

He also wrote not a few articles whose publication he paid for with the club’s account and which appeared as if written in different organs of the metropolitan press, which very reliably gave assurance that “numerous letters received from this important federal entity convinced them that the candidate in favor of that which they had dealt with several times, was the only one who could satisfy the noble aspirations of progressive Yucatecans”.

It was Luis Robles’s luck that the Gran Partido Liberal Porfirista would win in the contest with the Gran Partido Liberal and, with favorable responses to some previous letters to the Leader, he packed his belongings and came by the first steamship.

Today he was satisfied with himself as owner and master of his Fortune, walking again through the old theater of his student life and soon to give birth to “La Voz Pública,” an independent weekly, for which he would receive from the Treasurer General every month the sum of one hundred and fifty pesos. The newspaper would, furthermore, be recommended to all those who composed the large employees’ guild and, from then on, was counting everyone in the State Treasury Department as sure participants to whom it was very easy to charge subscriptions, deducting them when paying salaries.

What more could Luís Robles ask for? Defending the Government was an enterprise neither new nor difficult; and on the other hand, he had a sure entry with work so simple as the editing of “La Voz Pública,” a voice that would be heard only one day of the week; on all the others it would keep silent.

It was assured that the newcomer would waste no time in getting married. His fiancée was Antonia Pacheco, whom he had met and seen quite a lot of in Mexico City the past year, a beautiful and modest young woman, the only daughter of a man who was vulgar but loaded with money.

Luck, therefore, seemed to be smiling on the young man. He had already passed through prosperity’s doors and the world was his.