One Last Effort: Chapter Ten

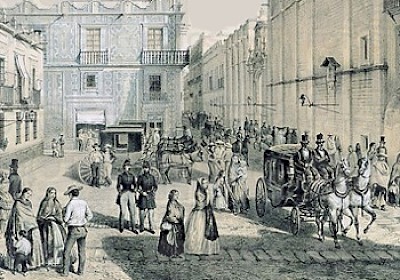

Luis Robles had gone to Mexico City. Making good use of connections available through a relative who gave him letters of recommendation, and a letter that he was able to get from his Law professor, he was hoping to obtain a scholarship that would allow him to live comfortably and somehow manage to continue in such a way that the big city would open a path for him, securing a respectable position in line with his aspirations.

After a lot of useless waiting around in the Ministry and continued persistence with influential acquaintances who met with him there, he came out in the end with the longed-for scholarship that ensured his stay in the nation’s capital. Going to class at times, and skipping the rest, Luis didn’t lose his sense of humor with the change of scenery, much less when that change offered a broader field for his inclinations and character.

He increased his connections, began to attend some gatherings of a certain type, donned his top hat, and in order to make himself look as important as possible, was no longer inclined to leave his frock coat unbuttoned.

As he was handsome, the new look and his free and easy air spoke well of him. He was kind to those he dealt with and six months after arriving, he was making his way around the city as if he owned the place.

With some young journalist friends, he had begun to frequent the editorial offices, where he began handling news, verbally at first and then written. He was bitten by the desire to appear in the press and was hoping to be paid later for what he was now providing for free, since his talents were beginning to be appreciated.

It was of this that doña Raimunda and don Hermenegildo were speaking in her home one night. The bachelor was not visiting doña Prudencia because she had fallen ill during the day, and that afternoon a high fever was consuming her to the point of making her delirious. It did not, however, seem to be anything of concern, so as he was not worried, he went to visit his friend doña Raimunda. The latter teased him that it was a matter of planning the wedding that was bothering doña Prudencia.

“Wedding plans, already? I don’t deny that I think I’m making progress. But wedding plans, there are none. Believe me, I know what I’m talking about.”

“But why don’t you speak frankly? I’ve talked with doña Prudencia and she tells me that you don’t show her your intentions with anything more than indirect statements. Why don’t you tell her once and for all that you want to marry her?”

“Señora, because I don’t have it in me, because I can’t control myself, because I don’t have the courage. When I want to tell her something, I get strangely agitated. I can’t avoid it. It’s like someone is going to kill me.”

“But those are childish things, don Hermenegildo. Make up your mind.”

“All right. I’m going there soon. I know what I’m talking about. Two nights ago I reminded her that with Lupita’s marriage, she was going to be left alone and that there wouldn’t be a better occasion for her to remarry.”

“And she?”

“She smiled. She’s very nice. Ay! But I wasn’t born for these things, doña Munda. I assure you that if all men were like me, not even half of them would marry.”

“Well, I’ve already talked with you about this and you told me it would be odd for her to propose to you. That means that it’s best left up to you and that you just need to talk with her.”

“Yes. I promise you that I’m going to talk frankly with her. But what will she think of my brevity? The first time that I speak clearly!”

The attention of the two visitors was caught by the arrival at doña Prudencia’s home of a carriage from which stepped the family doctor. A little later they saw that a boy who had come out of the house was running down the street with a bottle, and as he passed by he informed them that he was hurrying to the pharmacy because the señora was not doing well.

Don Hermenegildo went to find out what was happening and returned with the news that the widow was in serious condition.

“Ave María!,” exclaimed doña Raimunda. “I’m going over there.”

And after giving some instructions to the domestic help, she went to her friend’s house.

The doctor, after the examination and prescription, explained to the family that the intense nature of the fever was not very reassuring. He recommended that they take great care that she not miss a dose of the medicine, and promising to return soon, he took his leave. Doña Raimunda, who left there very late that night, attended the patient with true affection.

The latter’s condition was worse in the morning. The doctor said it would be wise to prepare for the eventuality of her death, and the difficulty was to find someone to break the news to her. Doña Raimunda resigned herself to the task, making use of cautious understatement, to which the patient responded by designating which priest she wanted.

Another worry, equally serious, assailed the ailing Prudencia in those moments: Lupita. What would become of her daughter, young and without maternal support? She begged them to call Pancho Vélez and she spoke with him in a voice weakened by her illness. He, who deep down was not a bad person and who blamed his habits and disorderly life on nothing more than a flaw in his education, was moved by the dying woman’s words and he of course promised to get married, after which he left the house ready to fix everything.

Once on the street he set himself to thinking about his situation, and it seemed to him he was in a fantastic position. He had decided to get married, because he had to do it some day and because his mother was always preaching to him about marriage’s convenience. But if one night he had set the date for his own marriage, it was so that he would not be left with nothing to say. The truth was that he had never thought seriously about it.

This time, the situation presented itself as inescapable. The sick woman wanted to see them united before she died. The poor señora! She had been very good to him. And in the end, if he had to get married, today was the same as tomorrow. Why not give the poor woman what she was asking for?

So on the following day, the ceremony was celebrated at home, in front of an altar in the patient’s room and in keeping with her insistence that she wanted to witness it from her bed.

The wedding was sad and hushed. Aside from the wedding party and witnesses, the only others in attendance were doña Raimunda, puffing due to her weight and the heat, don Hermenegildo, looking as if he was about to cry, and their neighbor Chonita, with a strange look in her eyes, probably making notes for her next liaison with her mechanic.

Doña Prudencia was crying, and every once in a while her moans interrupted the solemn words of the ritual recited by the priest. That celebration that is usually cause for a party and rejoicing therefore had the funereal aspect given it by the circumstances. Guadalupe was emotional and Pancho Vélez had a disgruntled look on his face.

The sponsors were the young man’s sister, as his mother excused herself with the rheumatism that tormented her, and Guadalupe’s brother, Manuel, who with his sullen and bad-tempered face and untidy mustache, had the look of a wild beast caught in a trap.

When the celebration was over, the widow called to her daughter, and sweetly drawing her toward her, the two embraced, intermingling their kisses and their sobs. Everyone present at this scene had the discretion to leave the room.

Lupita, who had watched the approach of her marriage and the seriousness of her mother’s condition as if she didn’t understand what either of those events signified, felt her very being diminished during the ceremony. And drawing near to the bed of the dying woman, who between tears snatched the opportunity to lavish her with caresses, more tender and effusive than ever, with the pain of thinking they were the last, her child’s heart, new to strong emotion, seemed to open itself to that first teardrop impregnated with deep sorrow, and a torrent of weeping arose from her young and beautiful face.

Chonita, who came to dispense a spoonful of medicine, interrupted the scene. A little while later, the bride conversed with the neighbors in the hallway, seated beside Pancho Vélez, although she constantly went to check on her mother, next to whose bed the surly, but sensible Manuel spent almost the entire day.

The following day, in the afternoon, doña Prudencia died. Numerous friends of the deceased and of Lupita showed up at the house of mourning, to say nothing of some friends of Pancho Vélez, who was now considered one of the bereaved. The neighbors were not to be missed. Chonita was there, doña Raimunda and her husband the señor don Felipe were there, and next to them the dutiful don Hermenegildo.

The prayers, the chocolates and the conversations followed as they do in such situations. Once past the initial impression that death produces, wakes resemble any other gathering place. People talk about everything and they laugh. Few are those who maintain a suitable circumspection, and of those there was naturally our most courteous don Hermenegildo, who was often engrossed in his own thoughts and who only once in a while spoke privately and haltingly with the señor don Felipe, who was at his side. Facing them could be seen the rigid body of the dead woman amid four sconces with their respective fat candles burning melancholicaly.

Doña Raimunda was calculating with her husband the likelihood that Pancho Vélez would inherit the estate, and the time that it would take him to exhaust it in riotous binging, when don Hermenegildo interrupted them, saying darkly:

“Can you see now, doña Munda, that I’m right in saying that I’m very unlucky?”“Why do you say that?”

“When I was thinking again of getting married and I was at the point of arranging everything . . .”

Doña Raimunda sprang up, and inasmuch as her volume would permit, she hurriedly got out of there so that she could give way to the laughter that was filling her cheeks and that she held back with a hand over her mouth.

As for the licenciado, half in jest, half seriously, he set about consoling the bachelor.

“Another one will turn up, don Hermenegildo. It’s a big world.”

“I doubt it very much, señor licenciado. Misfortune is my destiny. Believe me, I know what I’m talking about.”