Divorce in Yucatan

Years ago, when perusing the pages of eBay late one night because she could not sleep, Working Gringa happened to come across a little booklet that was for sale. She bought it, of course, and keep it in its little plastic sleeve because it seemed like a part of Yucatan's colorful history. Coming across it again recently, we read it and that led to more research about a particular little bit of Yucatan history.

About the Author

A.D. Melgarejo Randolph was an attorney who uniquely capitalized on the market for divorce in Yucatan. He was a former Supreme Court justice in Mexico, a judge in Chihuahua, an attorney general in Chiapas and an army colonel. He eventually came to the USA and had offices in New York, Sonora and Morelos. He published this book just one year after the law was enacted in Yucatan, and proceeded to make a career out of assisting in cross-border divorces. Eventually, he himself was sued for divorce by his wife Isabel, who cited cruelty. She accused Randolph of traveling to Mexico with starlets and other women seeking his services, and not sticking to business affairs. There was also some mention of demonstrating the Charleston in a Mexican cantina. In another unrelated incident, Randolph was taken into custody for his activity with Yucatecan divorces but was later released.

The Booklet

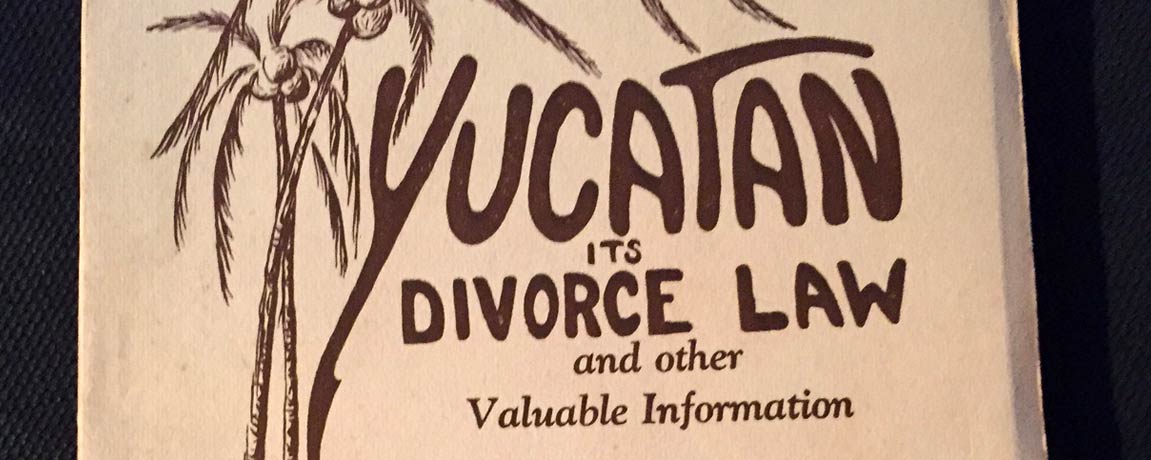

Yucatan, Its Divorce Law and Other Valuable Information... that's the complete title. It was published by International Publishing Co. in Los Angeles with a copyright date of 1924. It was written by A.D. Melgarejo Randolph who billed himself as "Attorney and Counselor at Mexican Law" and who wrote only one additional book, called Is Divorce Necessary? We will leave the answer to that question for another day...

Yucatan, Its Divorce Law and Other Valuable Information is dedicated thus: "To the honorable legislators of the State of Yucatan, for their liberality and wisdom enacting the actual divorce law of that Mexican State, the author of this book extends his compliments and dedication." With such affection, one has to wonder if maybe Señor Randolph perhaps had his own experience of divorce, from which he wrote this book.

After the title and dedication pages, there is a photo of the author, looking studious and professional in front of a fake backdrop of a bookshelf filled with large tomes, surely one of the first examples ever of a Photoshopped portrait (we jest, of course...).

He begins the book with a chapter called "As To the Validity of a Foreign Decision", arguing that a divorce in Yucatan is valid in the United States... just as valid, he claims, as a divorce obtained in Paris. In fact, he continues "...the procedure which in the State of Yucatan, Mexico is instituted for a case of divorce is more rapid than that in use in Paris...". Good to know! He goes on to explain how laws were different between the two countries ("For instance in Mexico it is lawful to deal in liquor; but in the United States it is not legal."), a patent reminder that this book was written when Prohibition was still the law in the United States. And then goes on to cite examples of when decisions in one country would be valid in another country, which are cases in which "the Positive Law agrees with the moral (sic) of both countries..."

In his next paragraph, he refers to a "well-known Cinema Actor of Hollywood" who went to Yucatan to marry. We have been unable to find any reference to an actor that may have married there in the 20's, but we are sure there were a few. After two more chapters arguing why or why not a divorce in Yucatan might or might not be valid in the United States, he gets down to the business of the procedure.

The Procedure

After stating his opinion that it is a crime to compel a man and woman who no longer love each other to remain married, he again reminds us that divorce in Yucatan is much quicker than a divorce in France... all you need are the proper documents. Of course, the words "proper documents" can strike fear in the heart of anyone who has ever applied for a visa in Mexico. As you will read later, there was no need for fear in those days... all the documents were not always necessary. The author tells us that the divorce procedure contains "only" 13 articles of divorce, each of which are based on the laws of Mexico which are not, he reminds us, related to the laws of the United States. And he reminds us how important it is to get a lawyer who knows the laws of both countries... and of course, he is one of those lawyers.

Thirty Days Residence

The first thing to know was that, though the laws of Mexico allowed for creating a Power of Attorney in most instances, in the case of divorce, at least one of the parties to the divorce must be in physical attendance in Yucatan. The law required 30 days residence in Yucatan, but you could spend "15 days in Progreso, 8 in Izamal and the last week in Merida, the place designated to get the divorce..." which sounds like a nice vacation, right? He reminds us that the person getting the divorce can spend the 30 days "visiting the thousand beauties of that old architectural part of the Maya Indians whose culture in those epochs excel all the tribes of the tropical regions of America."

Grounds for Divorce

Unlike in most states in the United States today, there still had to be grounds for divorce, even in Yucatan. Acceptable grounds for divorce included "Adultery; the fact that the woman had a child conceived previous to marriage; the moral perversion of one of the parties inciting the other to commit some crime; when the husband tries to force the woman to get money through prostitution; trying to corrupt the children by setting before them a bad example or consenting to their vices; by physical incapacity to fulfill the matrimonial functions; by the suffering of either parties of a contagious disease which may put in danger the health of the family; by abandoning the home without justifiable cause; by willful neglect of the children; by threats; by mistreatment; by accusing wrongly one or the other; by committing a crime punishable by prison; by habitual intemperance and finally, lacking all of these grounds, there is Mutual Consent of both parties."

The author points out that divorce by Mutual Consent was actually legal in all of Mexico, but that in most states, judges would require couples wanting a divorce that way to return to court on at least three different occasions, separated by at least a month's time, in order to see if they could "work it out". In Yucatan, he assures us, that did not happen.

Divorce Law Statutes

After opining that Mexican law is just too confusing for most people to understand, he points out that in most cases, divorces in Yucatan are effective immediately, allowing both parties to remarry again, but "there are many cases in which the woman is not able to get married until 300 days after the final decree." Looking back from the 21st Century, that seems rather discriminatory but he gives no reason for this.

He continues that matters of real estate law do not matter to Americans getting a divorce in Yucatan, as the laws of the USA govern their American real estate. The situation of any children of the marriage are, however, governed by the divorce decree in Yucatan. According to the laws of Yucatan at that time, "the youngest of 6 years must be in the care of the mother, provided she observes good conduct and without preventing the father the right of personal relations with them." The older children, between 6 and 14, could be given to whomever the Judge mandated, and the children over 14 were allowed to choose the parent they wanted to live with. And, he adds, the laws of Yucatan state that both parents must contribute to the financial maintenance of the children.

The History of Matrimony and Divorce

The next chapter in the book delves into the source of the word 'matrimony', saying, among other things, that "the mother works more than the father for the children, although she is protected by the father of the family, which as I have said, is the foundation of society." The following chapter deals similarly with 'divorce'. He says "When love which must exist between husband and wife, is lost, life becomes hellish. For this reason, divorce was instituted in very early times in order to avoid great troubles." He goes on to cite how divorce occurred in Hebrew, Greek and Roman cultures, most of which did not allow a woman to instigate a divorce. We can suppose those cultures only thought a loveless marriage was hellish for the man.

And with that, his discussion of divorce and procedures is over. On to the travel aspects of divorce!

As to the Geography of Yucatan

The next chapter extolls the virtues of Yucatan, explaining how the state is laid out. At the time, Quintana Roo was not a state, but merely a territory. The northwest coast of the Yucatan Peninsula was "made dangerous by the Campeche banks, a northward extension of the peninsula covered with shifting sands." The east coast, now the most popular part of the Yucatan Peninsula and called the Riviera Maya, he describes as "bluffs indented with bays, and bordered with several islands, the largest ones being Cozumal (sic), where Cortes first landed, Cancum (sic), Mujeres and Contoy." He adds that the bays are protected and would make a good place for shipping, but "It is, however, sparsely settled and has little commerce."

He talks about how Yucatan was discovered, what was left behind by the Mayas and that the Mayas revolted during the Caste War. "In 1910, there was another revolt with some initial successes, such as the capture of Valladolid, but then the Indians withdrew to the unknown fastnesses of Quintana Roo." What a great expression: "the unknown fastnesses". "The population of Yucatan in 1900 was about 306,000. The capital is Merida. The railways include the three lines of the United Railways Yucatan, 373 miles and a line from Merida to Peto."

About Merida, he writes "the population is around 65,000, the Maya element predominating." A particularly interesting passage is about the then-existing and crumbling Franciscan Convent, which "covers an area of six acres and is surrounded by a wall 40 feet high and 8 feet thick". That must have been something to behold... and something more to take apart, for as far as we know, it no longer exists in Merida. According to this book, it once held over 2000 friars, but their order was expulsed from Yucatan in 1820.

In Merida, he continues, they manufacture cigars, straw hats, soap, cotton fabric, hammocks and a "peculiar beverage called Extabentun (sic)". Lastly, he writes, "Merida is a modern and beautiful city; its streets are paved with asphalt and numbered; there are few names, because almost all are numbered. There are a few hotels run on the American plan; in general this city looks like any modern city of the United States. Everybody dresses in white, white shoes and panama hats."

Oh, what we wouldn't give to spend a day in THAT Merida!

His last chapter is a brief history and description of the "Indian Mayas", as he calls them. "Physically, the Mayans are a dark-skinned, round-headed, short and sturdy type, very intelligent. Although they were already decadent when the Spaniards arrived, they made a fierce resistance. They still form the bulk of the inhabitants of the Yucatan."

More From Smokeless Factories

The dissertation entitled "Smokeless Factories" (linked below) is a fascinating account of all the situations and implications of divorce between the USA and Mexico between 1924 and 1970. The author explains how Salvador Alvarado used divorce as "a direct assault against Catholic notions of morality", creating laws that expedited divorce. Under Governor Felipe Carrillo Puerto, divorce laws became even more liberal. Felipe Carrillo Puerto is famous for, among other things, divorcing his Mexican wife and planning to marry Alma Reed, a reporter from San Francisco, a plan which was cut short by his unfortunate death by firing squad in Merida's General Cemetery. Though there are rumors that he created the legislation to make his own divorce easier, his law was in fact framed six months before Ms. Reed even arrived in Yucatan and the book that started this inquiry and article was published just one year later. It is probable that Carrillo Puerto, often credited as the father of Yucatan tourism, recognized the possibilities for tourism in Yucatan that were created as a result of this law. Once the word got out, Yucatan obtained the reputation of giving the easiest divorce in the Western hemisphere.

Divorce Tourism

For a few years, Yucatan was famous for its divorce and many people traveled to Yucatan to obtain divorces. Many more people wrote to the government requesting information, including this request that reads like a typical inquiry to Yucatan Living or Trip Advisor in the 21st Century:

How often do boats leave and from where? What steamship line could I write to for information regarding boats? What accommodations could I get in Yucatan and what are the hotel rates? I would also like to inquire if one could catch a boat anywhere in Florida for Yucatan without making a trip to New York to get it?

These same questions are being asked today about airlines, hotels and even about ferries from Florida. In those days, ships sailed to Yucatan from Cuba, New York, New Orleans and even ports in Europe. Divorce seekers disembarked at Progreso, where they were given a physical exam to ensure that they were free from disease. After that, they had to get to Merida. If they were saving money, they traveled by a bolan, pulled by a mule. If they had more money, they took a train or a car powered by a Ford motor that held eight people (the beginning of combis, perhaps?). Once in Merida, many of them stayed at the Gran Hotel or at Hotel Colon, and they passed their days in Parque Hidalgo, strolling down Paseo de Montejo or taking a trip on the brand new highway to Chichen Itza.

In fact, the dissertation has a whole section on Divorce Tourism. Since, as the booklet pointed out, divorce seekers had to stay in Yucatan for thirty days, they ended up looking around. Yucatan capitalized on this fact, encouraging divorce tourists to stay in their hotels, go to the archaeological zones, etc.

We know a lot about the divorce seekers who came to Yucatan by the letters sent to the Yucatan government requesting divorce. The letters were mostly about how to get the divorce, or how to save money to do so. One woman apparently offered her services to give lectures on dental care in exchange for reduced fees; another man got the local Socialist party to petition the government for a fee reduction and obtained one. Divorces required certain documentation, but apparently the requirements were often overridden or not required, based on letters of petition to the government citing lack of funds or time or knowledge.

For a time, the divorce mill, as it came to be known, was a thriving business in Yucatan. Attorneys and others received advertisements in the mail about obtaining easy divorces in Yucatan, as there was apparently a loophole that allowed attorneys to solicit through the mail without being subject to the laws of any states. And as most people wanting a divorce were rather desperate, attorneys in Yucatan were able to charge what came to be exorbitant fees for their services. Also, apparently, there was an outcry against the Yucatan divorce mill on the behalf of (mostly) women who were being divorced against their will and without their knowledge until it was done. As many as 80 percent of divorces obtained in Merida during 1923 to 1926 were obtained by men, and nearly one third of all petitioners came from New York State, which had one of the most difficult divorce laws in the country at that time.

The Demise of Yucatan Divorces

So what happened? How did it all end? Apparently, by early 1926, the number of divorces obtained in Yucatan was dwindling dramatically. Felipe Carrillo Puerto, Yucatan's liberal and socialist governor, who had originally penned Yucatan's divorce law, was assassinated in early 1924. Within a few years, the conservative elite who were then back in power, introduced a new law that reversed much of Carrillo Puerto's legislation, changing the residency to six months and forbidding a divorce without the knowledge of both parties. Other states also changed their laws to become more competitive, including Campeche which could now grant a divorce with only twenty-four hours residency in Yucatan, strangely. In the end, according to the author of the dissertation, "The Yucatan Peninsula, then, once seen as the infallible panacea for American migratory divorce seekers, was the victim of an increasingly commercialized divorce business proferred by other Mexican states that fine-tuned their divorce mills based on the Yucatecan blueprint."

Yucatan played a strong role in promoting divorce tourism, and provided a beautiful, interesting and accommodating venue for divorce in Mexico. Divorce tourism was just one of the key efforts of Governor Felipe Carrillo Puerto to promote tourism in Yucatan, a stated goal of his as he tried to grow tourism to provide jobs for the Mayas who were no longer employed or enslaved on the rapidly-declining haciendas. Other Mexican states went on to provide migratory divorces for the next fifty years, until laws in the United States made it no longer necessary.

Though tourists no longer come to Yucatan for divorces, they do still come in the millions, a tribute to Felipe Carrillo Puerto's foresight and vision.