Ceguera de la selva

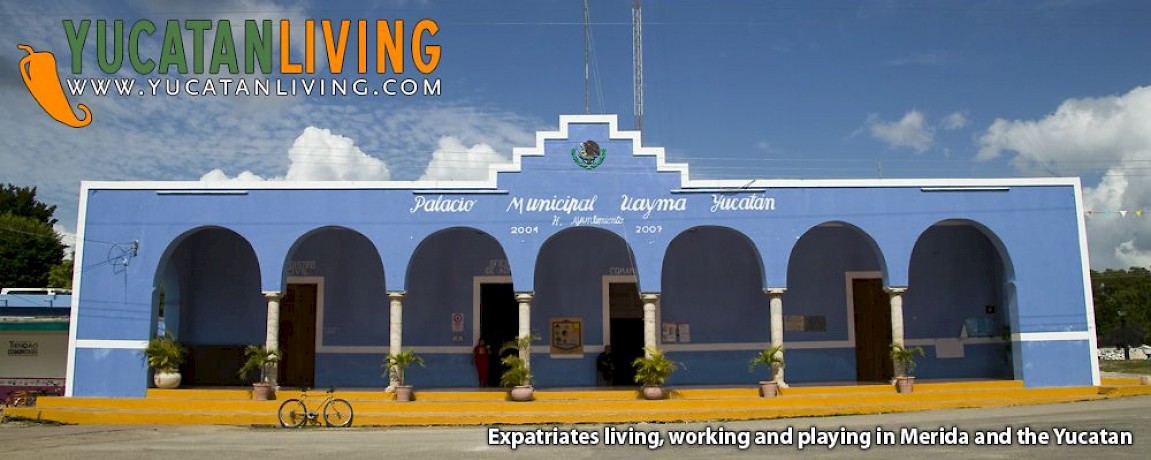

Tengo un terreno en medio de la selva maya, en un pequeño pueblo cerca de Valladolid llamado Uaymá.

Compré tierra aquí porque me encanta la iglesia. Pero poco después de mi compra, también me enamoré de la gente.

Miguel Xooc es mi profesor maya inconsciente y mi ayudante. Me llama regularmente para contarme cada detalle de lo que sucede en este pedazo de tierra aislado y abandonado por mí. Se emociona muchísimo cuando voy a visitar mi terreno. Me muestra todo el progreso que ha hecho para mantener la selva alejada de las pequeñas construcciones parcialmente destruidas de la antigua casa de la hacienda que solía estar ahí. Mientras yo no estoy, él lleva registro de todos los animales salvajes que ve y de todas las serpientes que mata. Incluso guarda sus pieles para mí.

Tuve que decirle que me informara en secreto de todos los detalles de lo que hace y especialmente que mantuviera cualquier piel de animal lejos de mi esposa, ¡porque nunca la convenceré de mudarse allá en nuestro retiro!

El fin de semana pasado, me dijo que había descubierto una cueva. Anticipó mis deseos de verla, así que creó un camino por la selva para que pudiéramos caminar con mi hijo y su amigo a explorar la cueva.

La cueva estaba a aproximadamente un kilómetro de la entrada del terreno, lo que significa que realmente trabajó duro para hacer ese camino. Mientras caminábamos, le dije a mi hijo que viera las orquídeas silvestres floreciendo en las copas de los árboles. Mientras mirábamos las copas, Miguel nos advirtió que cuidáramos dónde pisábamos y que tuviéramos cuidado con las espinas de una de las ramas de los árboles que había cortado antes.

—¿Cómo se llama este árbol, Miguel? —le pregunté.

Me dijo: “...es un Tzubim.” Seguimos caminando hasta que vi una rama idéntica y le advertí al amigo de mi hijo que tuviera cuidado con el tzubim. Miguel me corrigió de inmediato diciéndome: “No, Patrón, eso no es un tzubim, ¡eso es un chimmay!”

—¿Cómo voy a saber? —respondí—. Me parecen todos iguales.

Miguel no podía creer que no pudiera distinguir diferencias tan evidentes.

Decidió en ese momento que me iba a dar un recorrido botánico y empezó a nombrar y describir cada árbol que veía en este bosque tan denso.

“…Entonces, Patrón, este es un chaka. ¡Mira qué roja es la madera! Tiene una madera muy suave. Ahora, mira, este es un dzilzilche. Este tiene conchas muy bonitas alrededor de su tronco. Este es un chacté y tiene conchas más grandes alrededor de su corteza y tiene un chulul muy rojo.”

—Oye, Miguel, ¡para ahí! ¿Qué es un chulul? —Miguel se detuvo y se volteó hacia mí—. “Chulul significa ‘corazón’ en maya. El chulul del chacté es muy rojo y su madera es muy dura. Este de aquí es un bacabché. En este, el tronco es muy liso. No crecen espinas y su chulul es café.”

Luego Miguel se puso muy serio y me dijo: “Patrón, este es un chintoc.” Miguel me presentó este árbol como si fuera una persona. “Este árbol es tan duro que rompe hachas.”

Seguimos avanzando lentamente en el bosque cuando encontramos más de cincuenta flores tiradas en el suelo. Miguel me dijo que esas son las flores del piim. Me dijo que el árbol de piim tiene muchas espinas, y sus flores vuelven locas a las abejas. Luego señaló hacia arriba y ahí estaban: cientos de flores saliendo de las ramas como un milagro. Le pregunté a Miguel por qué las abejas se vuelven tan locas con estas flores. Él tomó una del suelo y me pidió que la oliera. En ese momento, me uní a las abejas en ese aroma increíblemente intenso e inesperado a vainilla que escapaba de esa flor.

Seguimos y señaló un árbol y me dijo: “Ese es un mahahual. La corteza de este árbol es tan gruesa que la usamos para envolver tamales.” Mientras caminábamos, pasamos junto a un tzubim y Miguel me dijo “por experiencia” que este árbol tiene espinas tan grandes que si pisas una, no puedes dormir en toda la noche. Seguimos caminando y pasamos un chimmay. Me dijo que el chimmay tiene “una madera muy, muy dura con un chulul extremadamente café” pero compensa esos defectos con frutos muy bonitos.

Mientras seguíamos caminando, describía árboles con nombres como pomoCHE, bacabCHE, chinCHE, ikiCHE, piniCHE y yaxCHE. Le pregunté por qué la mayoría de los nombres terminan con ‘che’, y me explicó que che significa ‘madera’. “La primera parte del nombre describe el tipo o el propósito de la madera que nosotros los mayas damos a un árbol. Una es ‘la madera que cura’, o ‘la madera que lastima’, ‘la madera para refugio’, ‘la madera para los dioses’.” Mientras describía las características de cada árbol, yo podía acercarme a ellos, mirarlos y tocarlos. Empecé a detectar sus diferencias sutiles mientras Miguel me explicaba para qué se usan.

Y entonces encontramos un chechen. Cuando me acerqué a ese árbol, un asustado Miguel me gritó que parara. “No, Patrón, no toques ese. La corteza es altamente venenosa. Si la tocas, te dará una comezón terrible y la hinchazón será insoportable.” Bueno saberlo.

Mientras caminaba y seguía impresionado por la altura de miles de árboles, no pude evitar preguntarle a Miguel:

—¿Cómo sabes tanto de todos estos árboles?

Miguel respondió:

—Todos somos maya... los árboles y la gente nacimos aquí. Para nosotros, conocer los árboles es como reconocer a un miembro de la familia.

Abrumado por la inmensa variedad y su conocimiento íntimo, terminé nuestro recorrido preguntando:

—¿Y quién plantó todos estos árboles?

Miguel, con absoluta convicción, respondió:

—Dios, claro.

En la vida real, Rodrigo Rodríguez es abogado para www.yucatanvisa.com.

Comments

Mirah 9 years ago

Thank you for sharing this article. I felt not only the deep love that Miguel has for the land, but was also moved by his willingness to share his ancient knowledge.

Reply

Toni 11 years ago

Love it!!

Reply

Peter de la Cour 12 years ago

Some months ago Rodrigo took me with him on a trip to view some properties he wanted to look at. One of the plots we saw was this one that he later bought. About 6 weeks ago Rodrigo invited me along with 4 other friends to see what progress he had made with the land and to show us it’s potential. We were met there by Miguel and his wife and daughter who prepared a delicious lunch for us. Rodrigo said he wanted to rebuild the hacienda building where only the somewhat dilapidated walls were standing, but otherwise pretty much keep the plot as it was rather than tame it and change it into a man-made design. He said: “It’s wild but beautiful and I want it to remain like thatâ€.

Miguel led the way and took us along the neat paths he had recently cleared in the jungle. He gave us a master class in tree recognition and tree lore. At first sight all the trees looked pretty much the same to me. All had rather thin trunks, were not very tall and the foliage seemed pretty uniform. But as he stopped before first one tree and then another, it became evident that they were in fact very different. He gave us the Mayan names of the trees and explained what their names meant. Then he examined the bark, the branches and the color, size, texture and odor of the leaves and the fruits. Soon it became apparent that the jungle is not only a living forest, but also a pharmacy, a food store, and a raw material for the construction of houses and the making cooking utensils, sculptures and other artefacts. The forest and the animals, birds and even insects who live there are not only a slice of real life, but also a source of myths, fairy tales and richly symbolic in many different ways. Several parts of the trees we examine had medical properties. Miguel pointed out that the bark of one trees was poisonous to humans and that we should definitely avoid even touching it.

Miguel had a deep knowledge of all aspects of the forest. It was evident that he felt completely at home there, and that he was communing with nature. When we left I had the pleasant sensation that I had made tentative friends with the trees we had examined. Miguel had taken cutting from several of them and neatly arranged them in rows in a tree nursery, so that he could plant more trees when he wanted to.

As we left Rodrigo and I decided that we would soon return, rent some horses and explore the forest on horseback. I am very much looking forward to this adventure.

Reply

Heather Hunter 12 years ago

A lovely article to have found on the internet today. I am going to stay in a rural village in Quintana Roo next month and am looking forward to learning about the area. When you wrote that your guide said be careful not to tread on something, I thought it was going to be a snake. Being from Canada I am not used to snakes and I am afraid of them but I am going to conquer my fear because I love the friendly Mexicans so much. Gracias.

Reply

Gene Kelly 12 years ago

Also very interested in becoming familiar with the Yucatan trees. Any advice or direction on where to find information? Building and intend to live in the jungle

near Tulum.

Reply

Madai Batres 12 years ago

Loved it!!

Waiting yet for the book! ;)

Reply

Jennifer 12 years ago

What a beautiful article! Looking forward to more.

Reply

Ayn Cabaniss 12 years ago

Interesting article! Would love to have seen some photos of individual trees and possibly some Latin or common English names to go with the Maya ones. Never was able to find a decent book on local trees while living in the Yucatan.

Reply

Profesor Mike Fehily 12 years ago

Captivating and engaging. A living reminder of how we city folk need instruction from our indigenous "teachers" about the life of the jungle. Their synergy with nature is truly an inspirational talent. I look forward to more from "Patron" Rodriguez and the tales of Miguel "the Mayan Professor" and especially about "the tree that cures". Which one was that?

Reply

(0 to 9 comments)