Laguna Bacalar, Special Waters

History of the Special Waters of Laguna Bacalar

In the southeast corner of Mexico, close to the Bay of Chetumal and the northern border of Belize, is Laguna Bacalar (Lake Bacalar). Spectacularly colored, with large submarine cenotes that feed it that clear water, with extensive uninhabited mangrove and jungle shores, Mexico's second-largest freshwater lake is located in the Yucatan Peninsula, just a few hours from Merida. Laguna Bacalar is remarkably beautiful with near-pristine waters, and it is becoming a favored destination for many residents of the Yucatan Peninsula who want to enjoy the weather, the beauty and the serenity of that area.

The lake has often been called La Laguna de Siete Colores, leaving one to wonder if the seven colors refer to the traditional light spectrum (ROYGBIV) or are a Maya reference to the water's seven shades of blue. Lying in a hammock on the shore and looking out over those pleasing blue waters, luxuriating in a cooling breeze, it is easy to imagine that people have been coming right here to do exactly the same thing for a long, long time.

When Did Mayans Come to Bacalar?

It might surprise you to know that experts cannot reach a consensus about an approximate date (even to the nearest couple of thousand years!) when humans came first to live along Laguna Bacalar. Until recently, it was generally believed that the Maya were the original inhabitants of Quintana Roo, establishing civilizations south of and in the Yucatan Peninsula between 3500 and 2000 years ago.

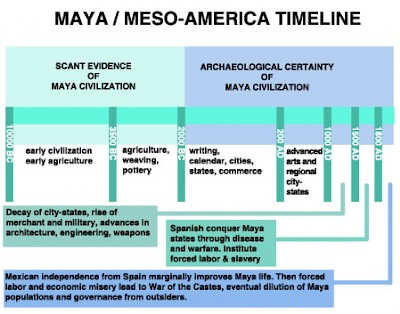

The various Meso-American city-states and cultures of the Maya rose to prominence in different eras and regions, creating a mosaic of power and influence that waxed and waned across central America over at least three millennia. Western scholars generally agree on a framework of Maya history that looks something like the diagram to the right. The Maya have a rather different framework for viewing this history, believing that their ancestors have been coming here for a much longer time.

Recently, archaeologists working in submerged caves and cenote systems near the Tulum seashore (in places that were as much as 30 meters above sea level at the end of the Pleistocene Era, just 11,700 years ago) have discovered artifacts that seem more in line with the Maya version of history. They have found human skeletons radio-carbon dated to be between 8050 and 11,670 years old. Research is incomplete and there is little that ties these humans to any specific cultural heritage. That said, some anthropologists can imagine an enduring and separate maritime Maya culture that was built upon the long-range coastal and freshwater canoe-borne trading known to occur through most of Maya pre-Colonial history. These mobile traders and wayfarers were from their regional city-states, but their sea-faring, trans-regional roles in trade provided them a wider worldview and a more arms-length relationship with their political, religious, and even commercial hierarchies. In other words, they may have identified as Maya, but they were also rather independent and roamed far from their original homes.

Location, Location, Location

Though it is not clear when they began, prosperous trade routes ran through Laguna Bacalar and traders (plus a population that supported that trade) inhabited the lake shores. It seems probable that Maya settlements became well established along the lake sometime between 4000 and 3000 years ago, whether or not these were aligned with a regional Maya power. Some histories propose that 1580 years ago, the Itzaes culture, known for aggressively establishing and managing trading networks that circumnavigated the Yucatan Peninsula, founded Siyaancaan de Bakhalal, the Maya port city of Bacalar.

Fast forward 1100 years. The Spanish subdue the local Maya and Gaspar Pacheco founds the colonial pueblo of Salamanca de Bacalar on the formerly Maya site, a process that is done all over the Yucatan Peninsula. Fast forward another 100 years and Bacalar falls to pirates, becoming a lawless trade outpost. After another 100 years, colonialists reclaim Bacalar, build Fuerte de San Felipe (San Felipe Fort) from deconstructed Maya monuments, and establish a mestizo culture. 130 years later, the War of the Castes kills or expels non-Maya and returns Bacalar and much of Quintana Roo to a purely Maya rule. Not for long, however. Because soon Federal Mexico regains control of Quintana Roo and the Maya rebels are quashed. 80 years after that, archaeologists discover Ixcabal, a vast Maya city complex comparable to Calakmul. It is only about 25 kilometers west of Bacalar, and the barely-explored site has hundreds of structures and a much larger and taller pyramid than El Castillo in Chichen Itza. For being situated on a low jungle plain with thin soil, no above-ground water and unforgiving weather, it seems to have been a curiously popular spot. Little is known about the culture that apparently thrived there, but perhaps it was related to the once-popular trade routes along Laguna Bacalar.

Trade Routes

The 110-kilometer peninsula/isthmus of Xcalak, east of the 65-kilometer-long Bay of Chetumal, provided a protected passage up the important Honduras-Belize-Yucatan water corridor. Archaeological findings and historical records indicate that this coastal passage was a core canoe trade route between the Maya states with access to the southern Caribbean coast of current-day Belize, Guatemala, and Honduras and the rest of the Yucatan Peninsula.

From the Bay of Chetumal, the large seagoing dugout canoes continued north in the lee of the Xcalak Peninsula and then through a cut (perhaps pre-Hispanic and man-made) and into calm waters behind the barrier reef along the Caribbean coast. Other local routes headed further north up into the Bays of Ascención and Espiritu, and from there, through inland waterways and a pre-Hispanic canal connecting the saltwater Chunyache Lagoon to the inland Muyil freshwater lagoon. Trade continued seaward along the coast past Tulum, Cozumel and Cancun and around the tip of the Yucatan Peninsula. This is where traders exchanged obsidian and other goods for valuable salt that is still produced on the northern parts of the Yucatan Peninsula. This would have been a one-way journey from Rio Motagua, Honduras, of about 1000 kilometers.

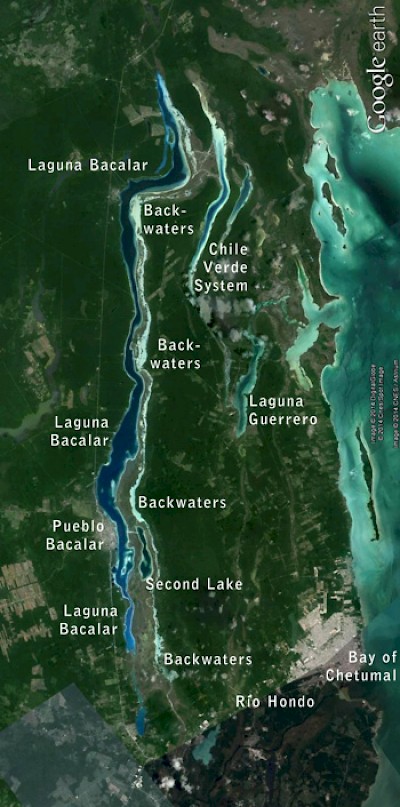

The Bay of Chetumal was probably an important way-point in the journey. It provided protection from weather, fresh water, and river access to inland trade. Geography shows us that from the Bay of Chetumal, mariners in paddlecraft can navigate fresh water to the upper reaches of the New and the Rio Hondo Rivers, providing access to northwest Belize. The Rio Hondo also provides access to Laguna Bacalar through the Canal Chac. It goes to a 15-kilometer freshwater riverine-and-flats system that passes through Huay Pix and is the principal exit of water from Laguna Bacalar. Approximately 52 kilometers long, Laguna Bacalar is fed by a few cenotes and many underwater springs. There are also several streams flowing into the lake from large seasonal marshlands to the west, north, and northeast of the far north end of the lake.

The Three Waters of Laguna Bacalar

It turns out Laguna Bacalar is not actually a single body of water. It is actually three irregular but parallel waterways that run more or less north to south, with a slight east-west slant. Close by is another lake-and-marshlands system, Chile Verde, that drains low-lying marshlands north and east of the lake into Laguna Guerrero and the Bay of Chetumal. The westernmost body of water is the largest and also the closest to civilization and Highway 307, and this is the water that is usually referred to as Laguna Bacalar.

If you head due east across the Laguna Bacalar from the town of Bacalar, you will pass through a 800-meter navigable cut called the Pirate Canal and into a second lake that is five kilometers long. That lake exits to the south toward the Canal Chac and eventually into the Rio Hondo. Here, the water ranges from one to fifteen meters deep, and the "Bacalar blue" water of this lake is very clear. The bottom is covered with light-colored sand or silt, and the shore is sandy with a few low shrubs and trees.

If you continue east across this second lagoon, you will pass through a half-kilometer shallow cut into a third lagoon of meandering backwaters with many narrow side channels. This body of water runs parallel to the main Laguna Bacalar for almost its entire length. It is a gently-flowing, shallow and clear waterway that is bordered on the west by low wetland flora and on the east by low jungle. Sometimes kilometers wide and sometimes only meters wide, these waters require some local knowledge to navigate, as it would be easy to get lost here. The waters are home to a number of bird and a few mammal and amphibian species. Strangely, there are very few fish in the lake. And also strangely, but wonderfully, in each of its many channels and passages, the water is extremely clear. The principal lake, Laguna Bacalar, shows vibrant blue colors with surprising variation in hue, not only from place to place but in one place from time to time, almost moment to moment. Whatever the reason, the blue of Laguna Bacalar has always seemed somehow special.

Blue is the Coolest Color

What about that blue color? For one thing, the shades of blue and the intensities of the colors change as tradewind-driven clouds come and go, often many times an hour during the day. And the lake presents different colors of blue in different places at any one moment, probably due to the varying water depth and bottom color and the viewer's height above water. The lake also presents different colors of blue at different moments of the day, probably due to changes in sunlight and turbidity, or suspended solids, in the water. One of the beauties is the changeability of the lake coloring; but mostly it's the blue. There is just a special "Bacalar blue" that seems to please everyone who sees it.

Many of us who live here have a special fondness for the blues of the Caribbean on a clear bright sunny day. Other people might love the blue found in deep ice or snow. The source of this special coloration and, as it turns out, the color of water itself, is a somewhat complex thing. In nature, the eye/mind sees specific colors because the object we look at absorbs some parts of the sunlight bathing it and reflects other parts. The reflected parts of the spectrum are what we perceive to be the object’s colors. That's the way color works for everything we look at in sunlight. Well, everything *except* water.

Water is unique in nature in that some sunlight is absorbed and agitates the water molecule’s electrons, causing them to radiate – not reflect – light at a specific blue frequency. This process is called vibrational transition. Water is the only naturally-occurring substance to exhibit this property and this may account for why the “special blue” of certain waters is so pleasing to the eye for many people. "Bacalar blues" are special colors. The clarity and mineral content of Laguna Bacalar, combined with the radiant blue the sun brings out, lend the lake an especially pleasing and ever-changing range of colors.

Generally, the deeper the water and the clearer the water and the brighter the light and the more reflective the bottom, the more vibrant the color your eye will see. So varying depths of similar water will yield different colors and intensities of blue. And varying whiteness of the lake bottom will also vary the color. As will varying light intensity, varying turbidity, varying sky color and cloud cover. Laguna Bacalar has all these things playing together, like an orchestra creating a constant symphony of blue, a spectral ballet. These factors combine, producing an astonishingly dynamic and beautifully-colored lake from moment to moment of every sunny day. We are not the first to be enchanted by these waters, and probably, we will not be the last.

****

Stay tuned for another upcoming article about traveling from Chetumal Bay to the north end of Laguna Bacalar. For almost ten years, Scott Wallace and his wife Peggy have operated www.bacalarmosaico.com, a website about Bacalar and Laguna Bacalar with information useful to visitors.

Read the second article, Laguna Bacalar, Back in Time

Read the third article, Laguna Bacalar Paddle Marathon