El Camposanto de Merida

Editor's Note: As the time for los Días de Los Muertos draws near yet again, we were reflecting, yet again, on the number of dead souls that would be called forth by their relatives in Merida on that popular day. We thought it might be time to revisit the oldest city cemetery, and update the things we have learned about the cemeteries of Merida since we first wrote this article many years ago. Enjoy, and as always, we welcome your comments!

Cemetery History

Early Sunday morning, after the dogs were walked at the Aquaparque as the sun rose, but before most of Merida had awakened, the Working Gringos found themselves down the street from their home in San Sebastian at Merida's oldest and largest cemetery. Like most cemeteries in Mexico, this one is more like a little city than an American-style graveyard. Back East in the United States, where people have been living longer, the cemeteries are more crowded than the ones out West where we are from, but they still don't come close to having the layers of history found in almost any Mexican cemetery. The Cementerio General in Merida is no exception.

According to our research, Merida's first cemetery was at Santa Lucia (at Calle 60 and Calle 55) beside the church that is still there. When that area became too busy, they moved the cemetery allllll the way north to Santa Ana (at Calle 60 and Calle 47). That too was soon engulfed by the ever-growing city, so in 1888, the cemetery was set up in its present spot in San Sebastian. They started by selling plots where the larger mausoleums were built that still stand today. These line the road from the main entrance on Calle 81-A with a resigned and faded elegance evoking an era of wealth. According to a friend of ours, many of these are not being kept up by their families because more and more people are choosing to be cremated instead of buried and the wealthier families don't feel as strong a connection to the past as they used to. Most of the newer generations of the older families whose names are on those buildings do not live in the centro historico anymore and rarely even come downtown. For this reason, also, when you want to see how los Días de los Muertos is celebrated, you won't find much to see in northern Merida. On October 31, if you go north, you'll see kids in Halloween costumes. Travel south of the Plaza Grande in the centro of Merida, and you'll see something very different!

The Cemeteries of Merida

And just to be clear, there are actually three separate cemeteries in this same area. Cementerio General has two entrances, on Calle 81-A and off of Calle 66 at Calle 95. Panteón Florido is a smaller cemetery with its entrance also just off of Calle 66 at Calle 95. Jardines de la Paz, a newer cemetery, has an entrance next to Cementerio General on Calle 81A. All the entrances are open approximately during daylight hours on most days, except for some holidays. Cementerio Xoclán, Merida's newest and most modern cemetery, is much larger and more park-like. There are facilities there for funerals, memorials and for cremation. At Xoclán, if you don't have the money for a large plot, you can lease one for three years. After three years, the bones of the person buried in the plot will be dug up, deposited into a special box called an osario, and the box will be put in a smaller space that costs less. There is also a communal grave for those without families or the money to be buried somewhere specific. Cementerio Xoclán can be found by going east on Calle 65-A, past Avenida Itzaes. The street name will turn into Juan Pablo II, and Cementerio Xoclán will be on your right.

Cementerio General: A Peaceful Place, Full of Stories

What drew us to the cemetery the morning we were there wasn't much other than a chance to stroll in peace. We drove into the main entrance and headed straight down the wide avenue and parked just past the glorieta (traffic circle) in the center. At this intersection, one of the first things we saw was the monument built to the leaders of the Socialist Party, with the elevated tomb of Felipe Carrillo Puerto, former governor of Yucatan. Felipe Carrillo Puerto was shot by a firing squad for his socialist leanings which did not endear him to the capitalist elite of Merida at the time. Just across the street and underneath an old shade tree is a rectangular sculpture that marks the grave of his famous lover, Merida's most important gringa (so far...), Alma Reed. Alma Reed fell in love with Carillo Puerto when she came to Merida as a reporter. Despite many complications, they planned to get married, and Ms. Reed was in San Francisco preparing to return for her wedding when she got the news of his death. At least six of Felipe's brothers and sisters are buried around him too, as well as other movers and shakers of the Partido Socialista del Sureste (the Socialist Party of the Southeast). One of those sisters, Elvia Carrillo Puerto, was a feminist before the word was invented, was the first woman to be a state Senator in Mexico and is almost as famous in the Yucatan as her brother. She is also buried there. Alma Reed died in Mexico City years after all the Carrillo Puertos, but requested that her ashes be buried near her famous lover. Que romantico, no?

Association in Death

Behind that memorial is another one built for the Sociedad Artistica. Guty Cardenas, perhaps Yucatan's most famous singer/songwriter, died very young and is buried here, along with a number of fellow musicians and singers from the late 19th and early 20th Century. Just down the road from all of this, the cemetery workers were gathered, resting before starting their day of keeping the cemetery somewhat free of basura. They were surrounded by a pack of dogs, who appeared to be their able-bodied assistants and certainly help with any edible basura. We are pretty sure there is no monument to the cemetery dogs, but perhaps there should be, as they are a ubiquitous presence.

The Dead and the Living

We spoke briefly with Lupe, a woman who sells flowers in the center of the cemetery (there are a collection of flower stands there, $30 pesos for two bunches the day we were there), who told us she loves her work. She loves the peacefulness of the cemetery and she has been working there every day for... are you ready for this?... fifty-seven years. She started working there when she was seven years old.

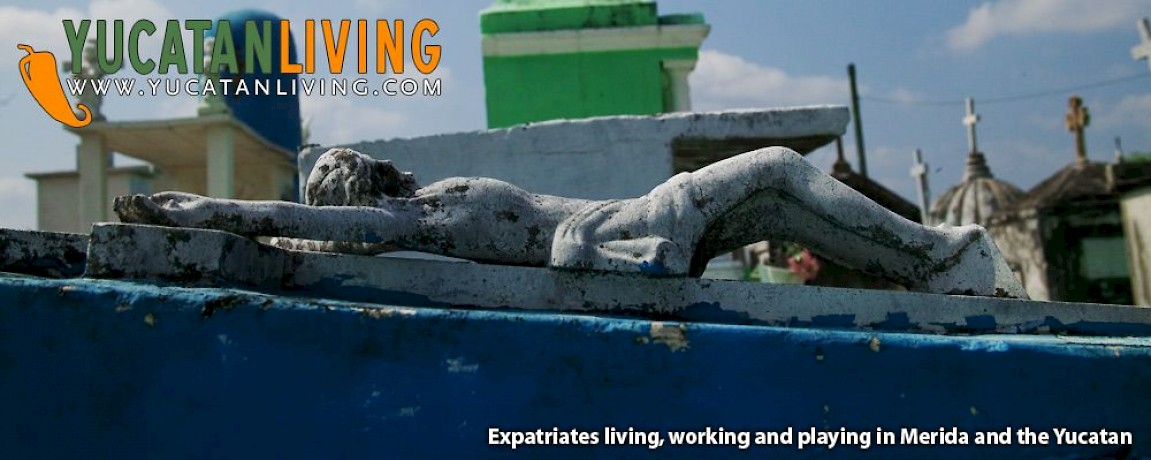

Cruising the cemetery, or camposanto (saint field) as it is also known, could turn into a lifelong occupation. This cemetery is huge, crowded, labyrinthine and mysterious. Just like in life, the main avenue is lined by the houses of the wealthy casta divina families, but instead of houses, there are mausoleums. They range from classically beautiful to over-the-top displays of wealth, but they are all filled with the same thing: restos (remains). The twin hammers of sun and rain, with occasional beatings by Category 4 hurricanes, make maintenance a never-ending (and in this case, multi-generational) chore. We think at least one of the families actually employs someone just to maintain their mausoleum because when we looked inside, we saw a freshly-oiled tricicleta parked amongst the crosses and flowers.

Even bigger than the mausoleums are the grand old trees. For us, their beauty and shade are a big part of what makes a visit here so lovely, especially when they are all flowering. The day we were there, we enjoyed quite a few trees that were just dripping with pods and flowers, lazily waving their branches in benediction over the dead buried around them.

And the dead are everywhere. Everywhere you look, there are houses for the dead. Big fancy houses, small modest houses. Some have what we think of as traditional headstones. Some people are buried in groups, like the musicians or the henequen workers or the Masons. Most are grouped with generations of ancestors who died before them.

Very few dead Meridanos rest in peace alone. You can walk between the rows and peek into the back of the small tomb-houses which seemed to be dedicated to just one person. But look closely inside and you will often see stacks of osarios, boxes full of bones. The bones of generations, buried one on top of the other. In fact, in a family-owned plot, the most recent body will be buried in the ground. That usually involves digging up the old bones from previous generations, which are then put in those osarios, to make room for the next generation.

It gives one pause.

Home Away From Home

You would not call most of the markers you see in Merida's cemetery 'gravestones' or 'headstones'. They are indeed little houses, built by the living for the dead. They bury the bones beneath or inside the houses, but the houses are kept as a place to visit. Most of the houses have windows and doors. They are often topped by crosses and angels. Inside each little house is something different, something brought and left by the living when they visit: statues of saints, photos, candles, flowers... even cans of beer, coke or pieces of candy. We suspect some might even leave meals but those are soon disappeared by a passing cemetery dog. Some of the houses are painted in bright colors, while others are kept clean and white. You can see that some families have planted trees on their plot, while others are planted with plastic flower arrangements. Anything that isn't living soon looks faded and dirty, beaten down by those twin hammers we spoke of earlier. Such is life.

The day we were there, we happened upon a group of women, obviously related, washing down a grave with bleach and soap before they put flowers in the vases. They were visiting their younger sister, they told us. She had died nine years earlier in childbirth. They came out today to clean her house and give her fresh flowers. They talked and laughed while they were cleaning and arranging, and then proudly stood for a group photograph after they told us Ella esta lista! (she is ready!). Having lost a close family member a few years ago ourselves, we can appreciate the grieving that must still go on, and the healing energy that this group activity must provide to these sisters.

Dust in the Wind

After walking around for an hour or so, we began to appreciate how taking care of the dead is a losing proposition for the living. Most of the little houses have broken windows and rusted gates. The candles are burned out and melted, the once-live flowers are dead and the plastic flowers are faded beyond beauty. The stones are cracked and falling apart and the bones are turning to dust. Statues of Jesus are missing body parts and angels are missing their wings. Some houses are newly painted with bright colors, but so many of them are faded and grey. Walking amongst them, you realize that the houses and statues are there for the people left behind, who need a place to mourn, a place to care for and nurture the missing. And when the grief has lost its rabid bite, and the lives of the survivors have become accustomed to the dull ache of loss, the houses fall apart, not because the dead aren't really there, but because the living have continued to live. In Mexico, each year the dead are revived, revisited and remembered during los Días de los Muertos, a very important holiday here at the end of October and beginning of November. Until then, the cemetery sleeps under the hot Yucatan sun.

And every day, the sun shines, the rain falls, the people pass, the dogs wander, the wind blows and the trees wave their benedictions down on the memories below. Gracias a dios! Viva la vida!

****

For more information on how Day of the Dead is celebrated in Merida, click here for one article, with links to more at the end.

Comments

Anita Saganich 18 years ago

Hola, kind people, Thank you for answering my e-mail about the possibility of second hand furniture. We are so excited about our home in Chuburna, and our move in September. We have been on the road now for over six years, and it will be wonderful to have a home that doesn't move. That sounds as if I am tired of our wonderful life, I am not. I believe the Father has other plans for us. We will need all the help we can get.

Reply

Genny M/La Peregrina 18 years ago

Hi WGs.

I see that you went to visit Alma Reed's tomb, next to her life-long lover Felipe Carrillo... it is very interesting. There is a movie with Antonio Aguilar (portraiting Felipe) about his life and encounter with Alma and the song Peregrina by Guty Cardenas and Ricardo Palmerin came along. Maybe you can rent the movie at a local Video-store. It takes you back in time. Regarding the cemeteries, most of them are alike. If you ever visit Hoctun, my parents hometown, you'll see a mansoleum for the Moguel Family. It goes back a century. My greatparents and grandparents, uncles, rest there. We go visit them every time we go to Hoctun. Thanks again for the memories.

Reply

Khaki 18 years ago

I once lived across the street from a cemetery in another town in Yucatan. From my upstairs window, I could see over its wall. The women do come to clean and keep things in order... but - very early on weekday mornings, it is the men who come, hat in hand - before work - to speak to a parent, or a wife, or a child... just for a few minutes - to say a prayer - and then go silently on about their business. This is a part of Yucatecan culture most people never see.

Reply

« Back (10 to 13 comments)